1 Battery Optimizations

1.1 Introduction

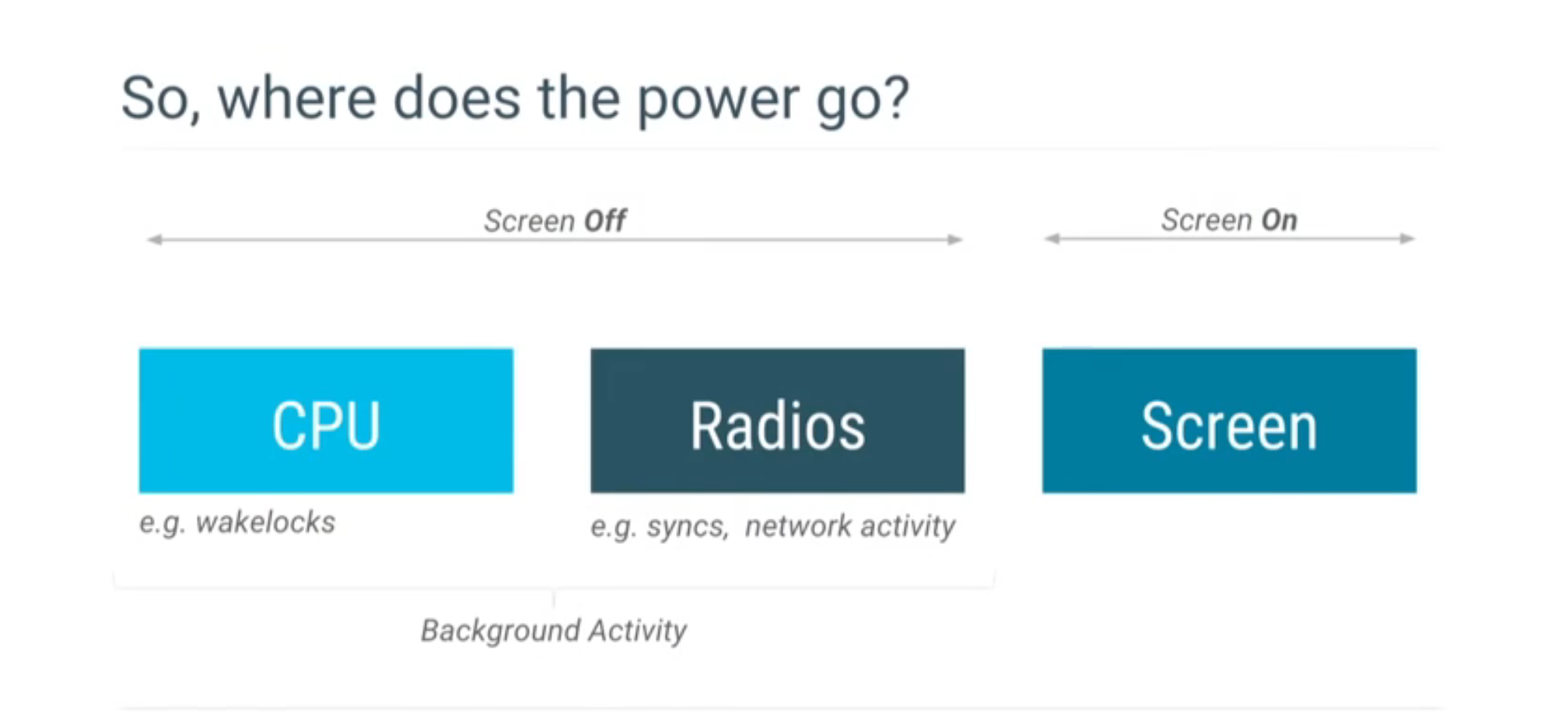

Where does the power on our mobile phones go?

Turns out, when the screen is on, it dominates the power consumption on your phone more than anything else. When you have your screen on, you’re either playing a game, or watching a video, or maybe you’re surfing the internet. And screen turns out to be a very expensive component on the device, which is many orders of magnitude more, in terms of power consumption, than most components on the device.

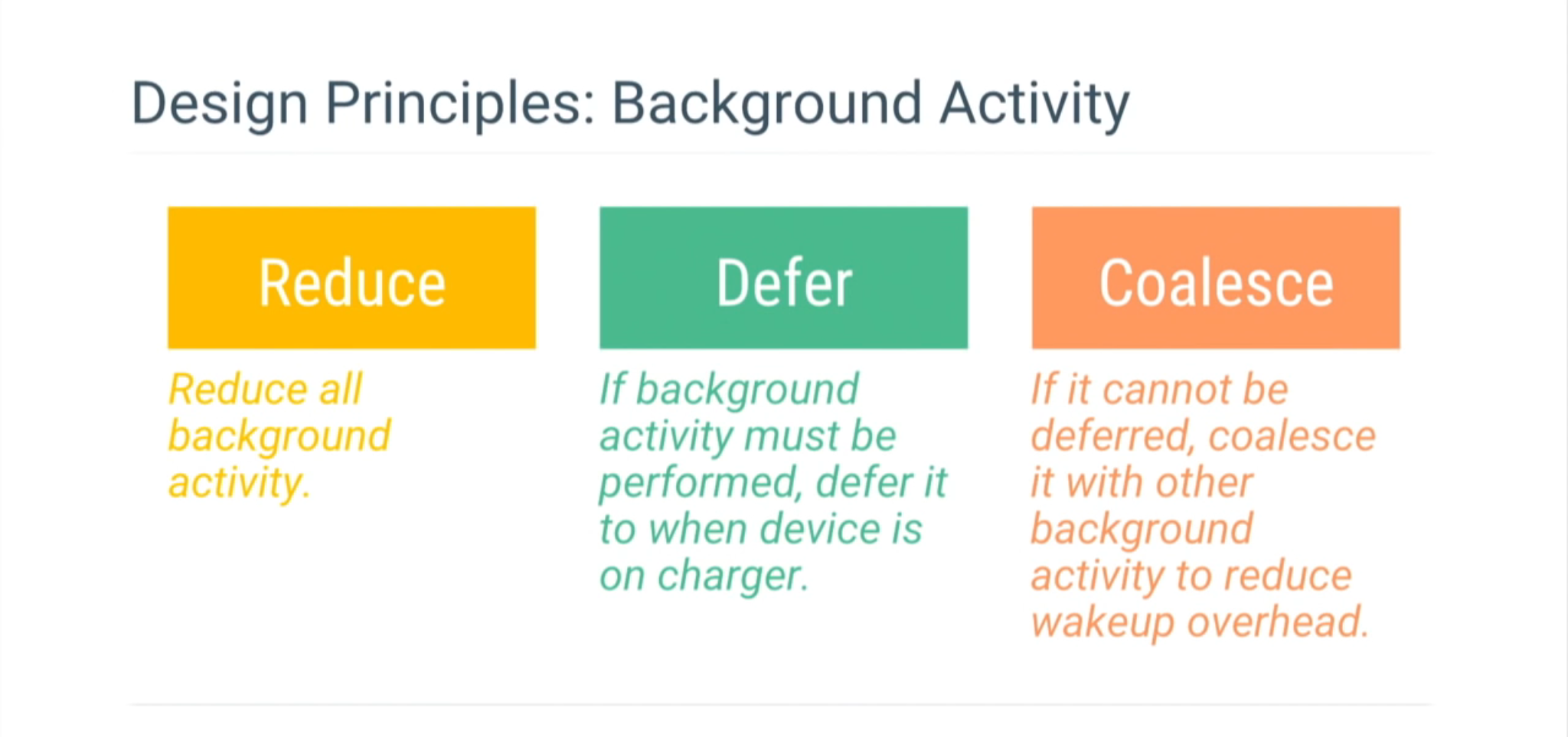

But our phones also spend a lot of the time in our pockets when the screen’s off, so when the screen is off and the user is not actively engaged or interacting with the device, the power consumption now starts getting dominated by the CPU and the networking radios. So it might be an application holding a Wake lock to do some activity. Or there might be a background job, or background sync, trying to access the internet to sync some data in the background, and all of that costs power. So when it comes to optimizing for power when the screen is off, the main design principles: Reduce, Defer, Coalesce any and all background activity that you can.

- Reducing the background activity for an app when the user is not actively engaged, or is not actively using the device

(application developers). - If background activity must be performed, defer it to when device is on charger.

- If it cannot be deferred, coalesce it with other background activity to reduce wakeup overhead.

1.2 How to Defer and Coalesce

JobScheduler API

JobScheduler API that lets Android batch and coalesce a lot of the background activity, in order to make the most efficient use of the CPU and the background networking traffic. – we talk about later

Doze

Doze which tries to coalesce a lot of that power background activity on the screen off, on battery, stationary state.

- [M-release] At some point, the device actually has been stationary for quite some time, so the first phase of Doze kicks in and this stays there for an order of tens of minutes.

At this point, applications lose Wakelocks, Network Access, and there are no more GPS or WIFI scans.And their Jobs and Syncs and Alarms get deferred until the next maintenance window.

So maintenance window is where all that background activity get coalesce to. This is where all these restrictions are lifted for a brief period of time for applications to be able to perform any kind of pending background activity to refresh the content.

When the device continues to be stationary, on battery with the screen off, the repeated pattern where the Doze windows are growing exponentially with maintenance windows in between. And this will continue until the Doze time, the green bars get to about a few hours.

Note: The orange bars are some kind of the background activity.

-

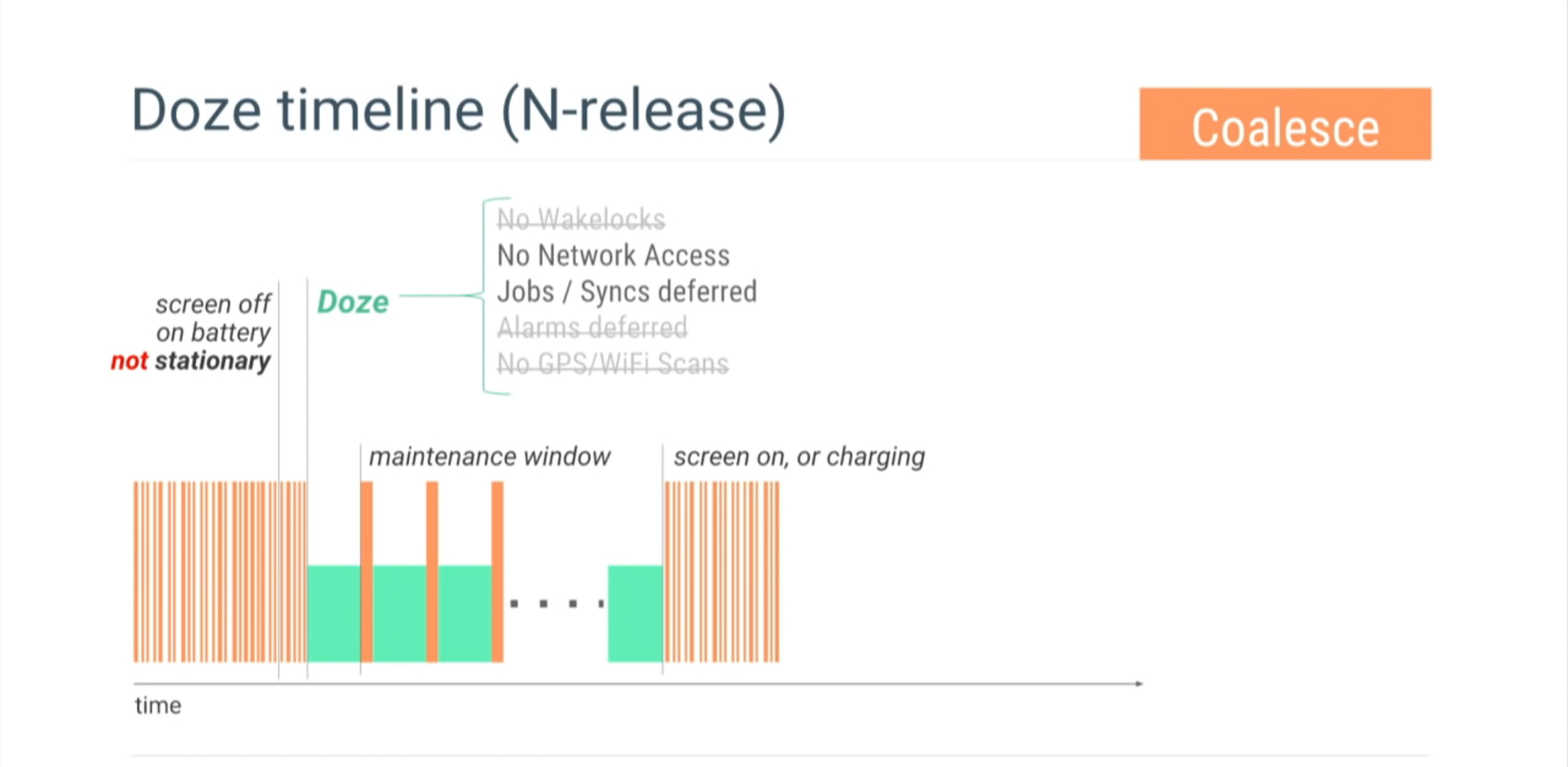

[N-release]

[1]. At some point, you turn the screen off, and you put the phone in your pocket, so it’s not being charged right now. Shortly after that, and this time on the order of minutes, so shortly after that,

the first phase of Doze kick in. And now, this is a lighter, gentler Doze than what you saw with Marshmallow in that it’s only going to restrict the application’s network access, and any of these jobs and syncs will get deferred to the next maintenance window, sort of the familiar maintenance window and Doze repeated cycle will ensure after that so long as the screen continues to be off.And in the maintenance window, these restrictions are lifted to allow any pending activity to resume. And all this will end when the screen comes on, or you plug in the device, as you would expect.

*

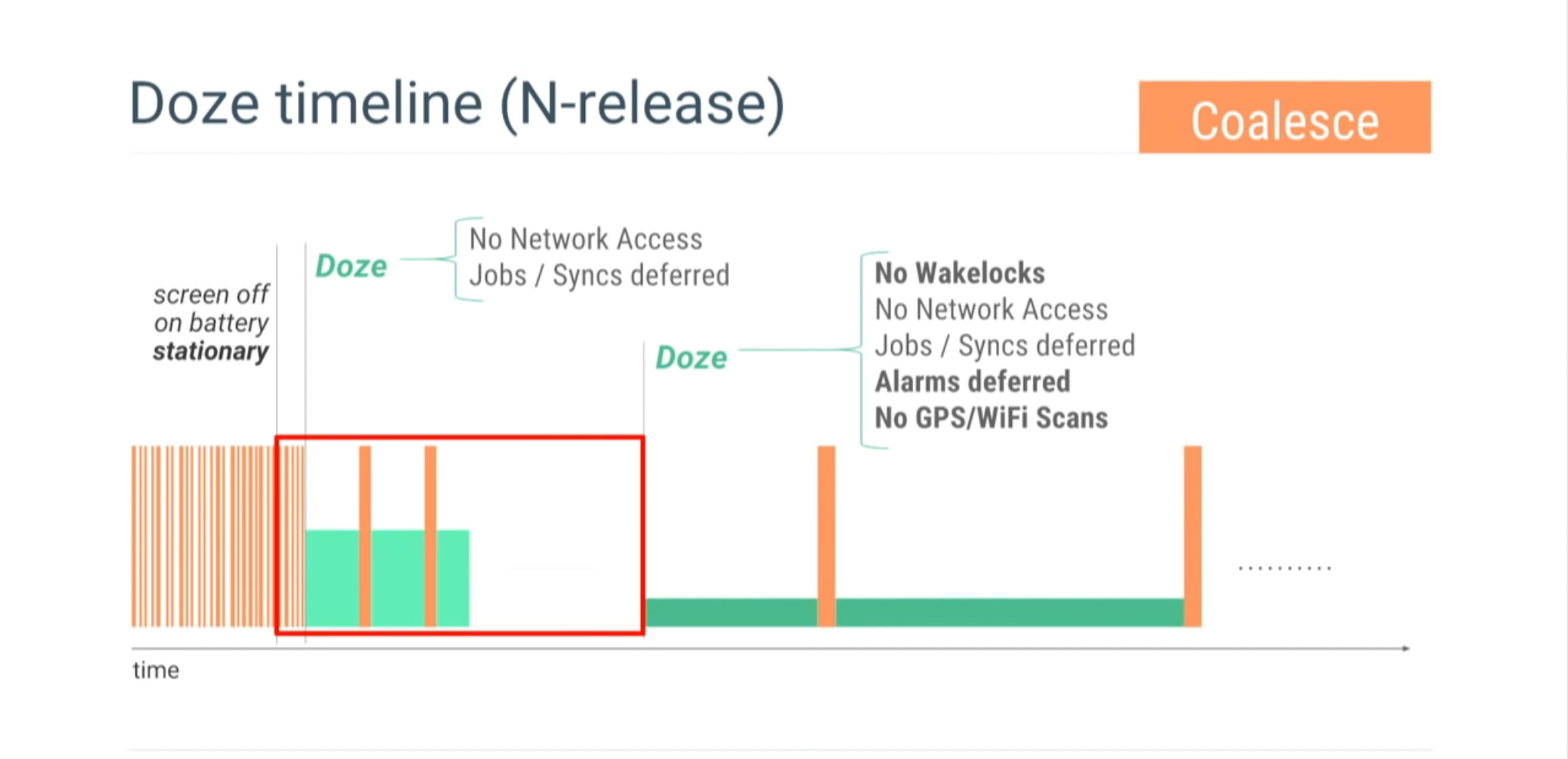

[2]. Instead of Marshmallow Doze status, the device is stationary, it’s on battery and screen off. But the amount of time hasn’t passed yet for Doze to trigger; only a few minutes have passed. At this point, this extended Doze, or this lighter, gentler version of Doze will kick in, the N-release. And you’ll see that same pattern of Doze and maintenance window. And at some point, the device will realize it has been stationary for quite some time, and it’s been stationary for the amount of time required for Doze to kick in. And then, at that point, just like it does in Marshmallow, the full set of Doze restrictions will kick in. So at that point, applications will lose Wakelocks, their alarms will get deferred, and there’ll be no more GPS or Wi-Fi scans because the device has been stationary.

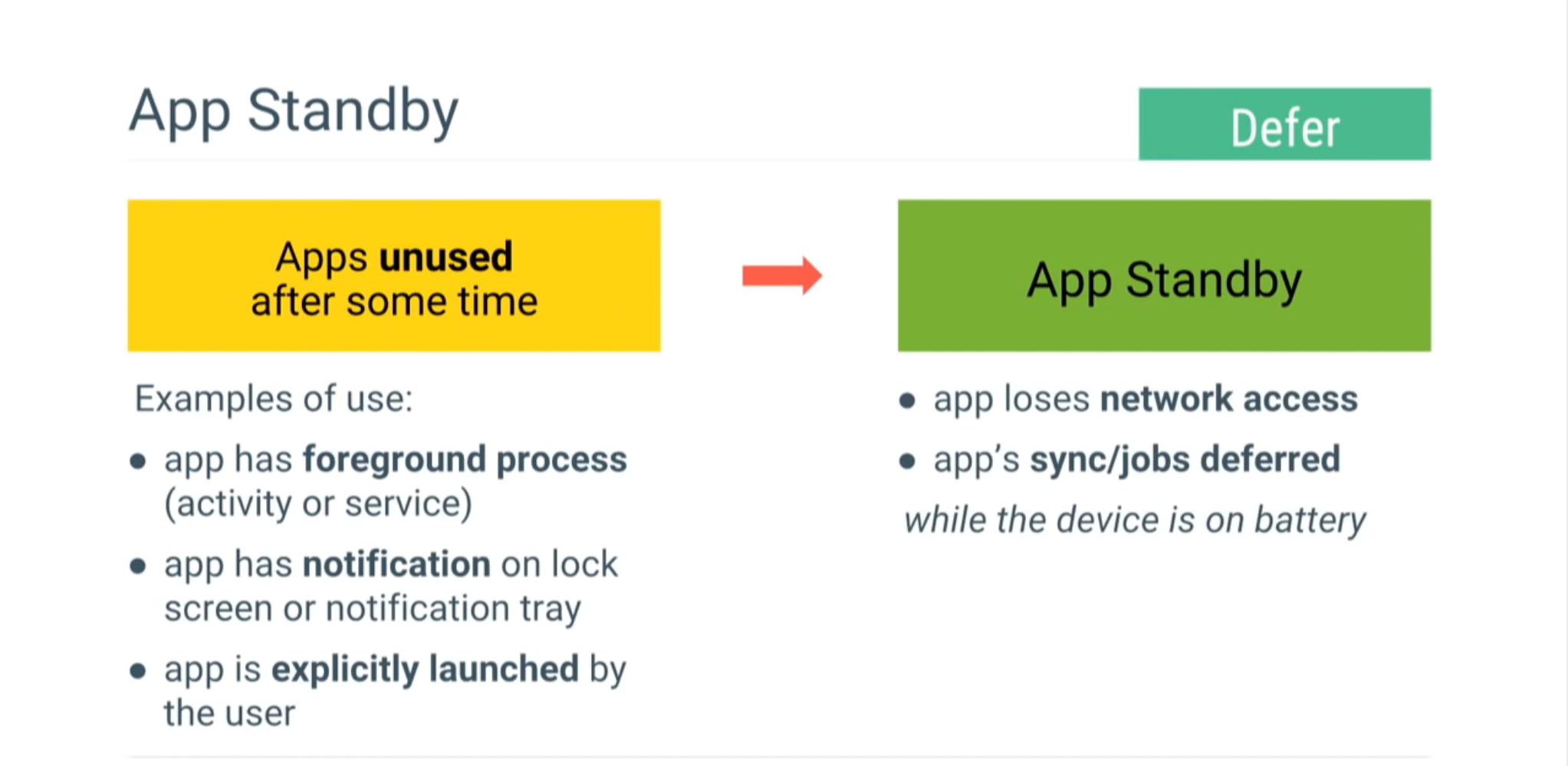

App Standby

App Standby which improve the power consumption of applications that you haven’t used over a period of time.

Apps that are unused after some period of time get considered to be on standby. It means applications that have had a foreground service; some kind of activity or process, they have had a notification on lock screen or notification tray; or app is explicitly launched by the user. And if this hasn’t happened over a period of time, then that application loses network access, and its jobs and syncs are deferred while the device is on battery. So they’re deferred to when you plug in the device.

But once you plug in the device, if the application is still not used, then it will still be considered standby. And the next time you unplug the device, it still, again lose network access, and its jobs and syncs will be deferred to the next time the device gets plugged in.

As the part of Doze and App standby, we launched something called a high-priority Google Cloud Messaging message, which now is Firebase Cloud Messaging. This high-priority messaging is a push message that grants the application can receive incoming instant messages or video calls etc. FCM have some functions as below:

- Grant apps temporary wakelock and network access

- For use cases requiring immediate notification to user

- Normal FCM messages batched to maintenance window

Note: For the devices that don’t have Google Play services, Google actually ship Doze and App Standby disabled by default in AOSP. And they instruct device vendors in markets where Google Play Services is not available to work with their ecosystems to identify an alternate cloud push messaging service. So we don’t have them enable Doze and App Standby unless they have Google Play services, or some alternate cloud-based push messaging service.

国内推送服务:小米推送,腾讯信鸽推送,百度推送,极光推送,友盟推送等。特点:免费,服务会被杀死,多个app共用一条 推送通道(共用即一个app推送服务被杀死,那么只要用户打开其他使用推送服务的app,其他app的推送也能接收到消息)

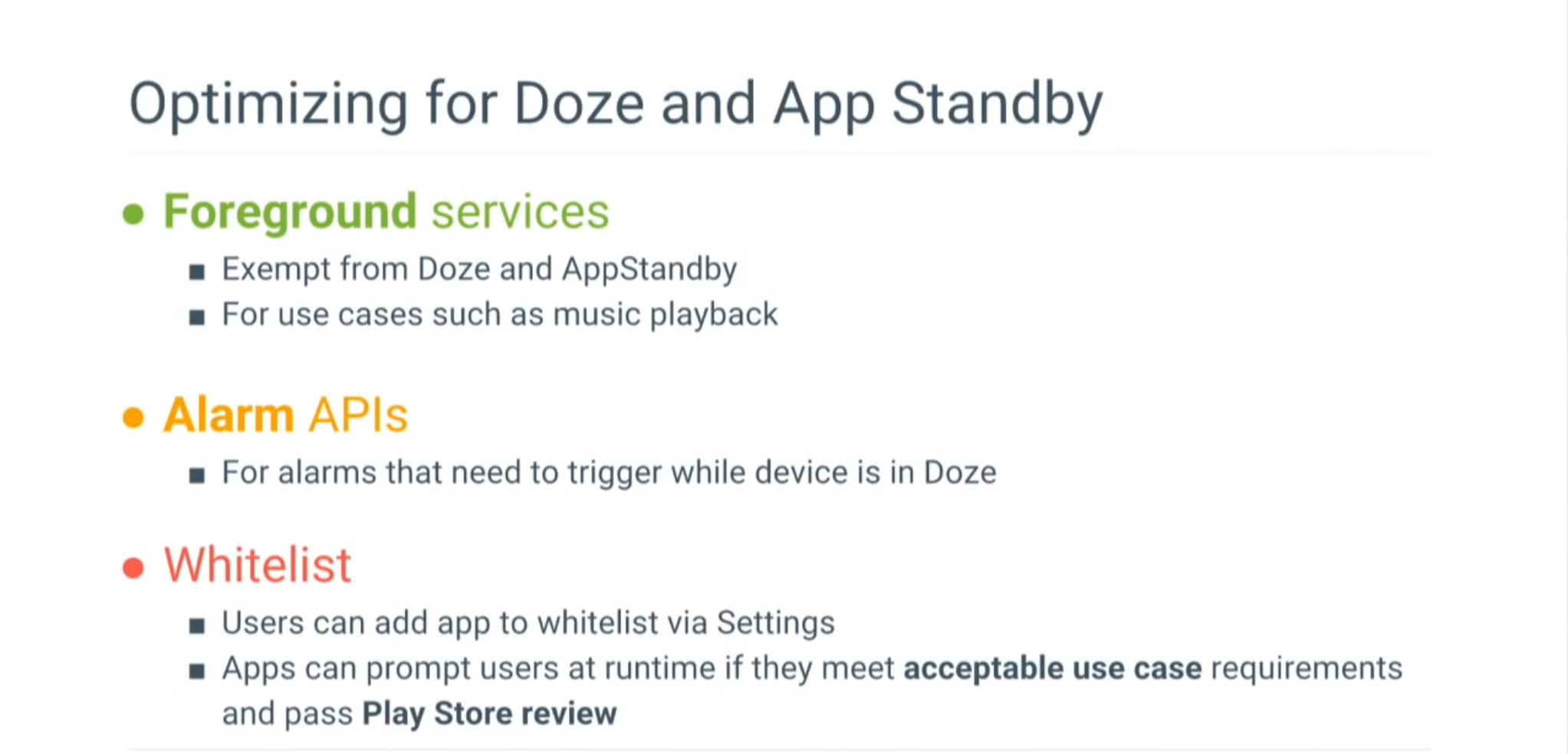

Of course, Android optimizes Doze and App Standby for some special use cases:

The foreground service such as music player which has to have a persistent notification, and such a service is going to be exempt from Doze & App Standby, so even though your device will enter Doze, this service will retain its network access and wakelock access.

And maybe some use cases where alarms are important, part of what the application needs to do on behalf of the user. So for those kinds of use cases, Android launched new alarm APIs that will trigger in a limited way during Doze.

And finally, for use cases that cannot be accomplished by Doze and App Standby, Android have a Whitelist on the system that users can add applications to that will cause the application to be exempt from Doze and App Standby. Applications can also prompt users at runtime to be added to this Whitelist, but this is only for very specific, narrow, acceptable use cases. And doing so would trigger a Play Store review before your application gets published to the Play Store.

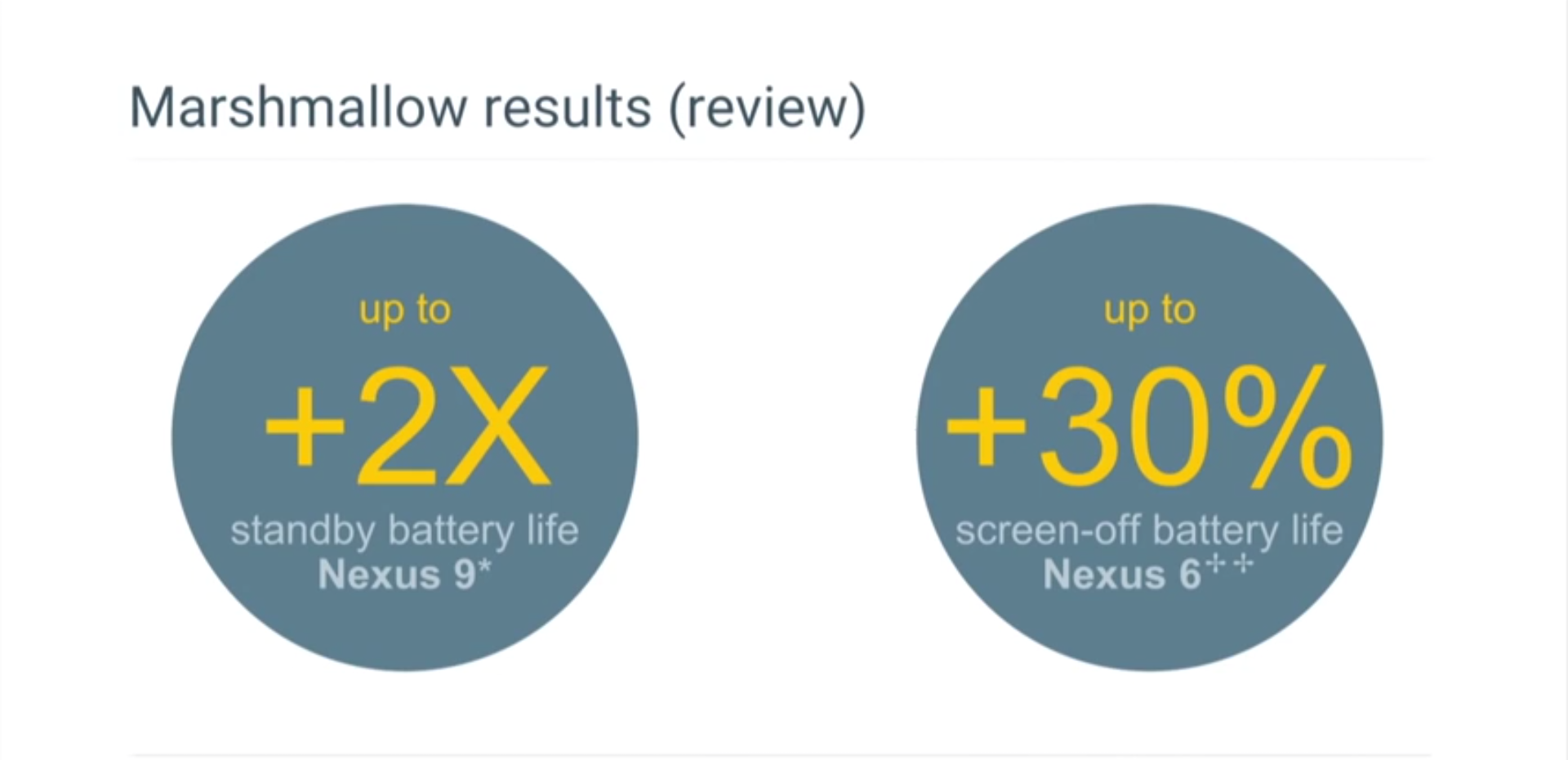

Doze and App Standby combined together can increase the standby battery life of Nexus phone as below:

2 Memory Optimizations

2.1 Introduction

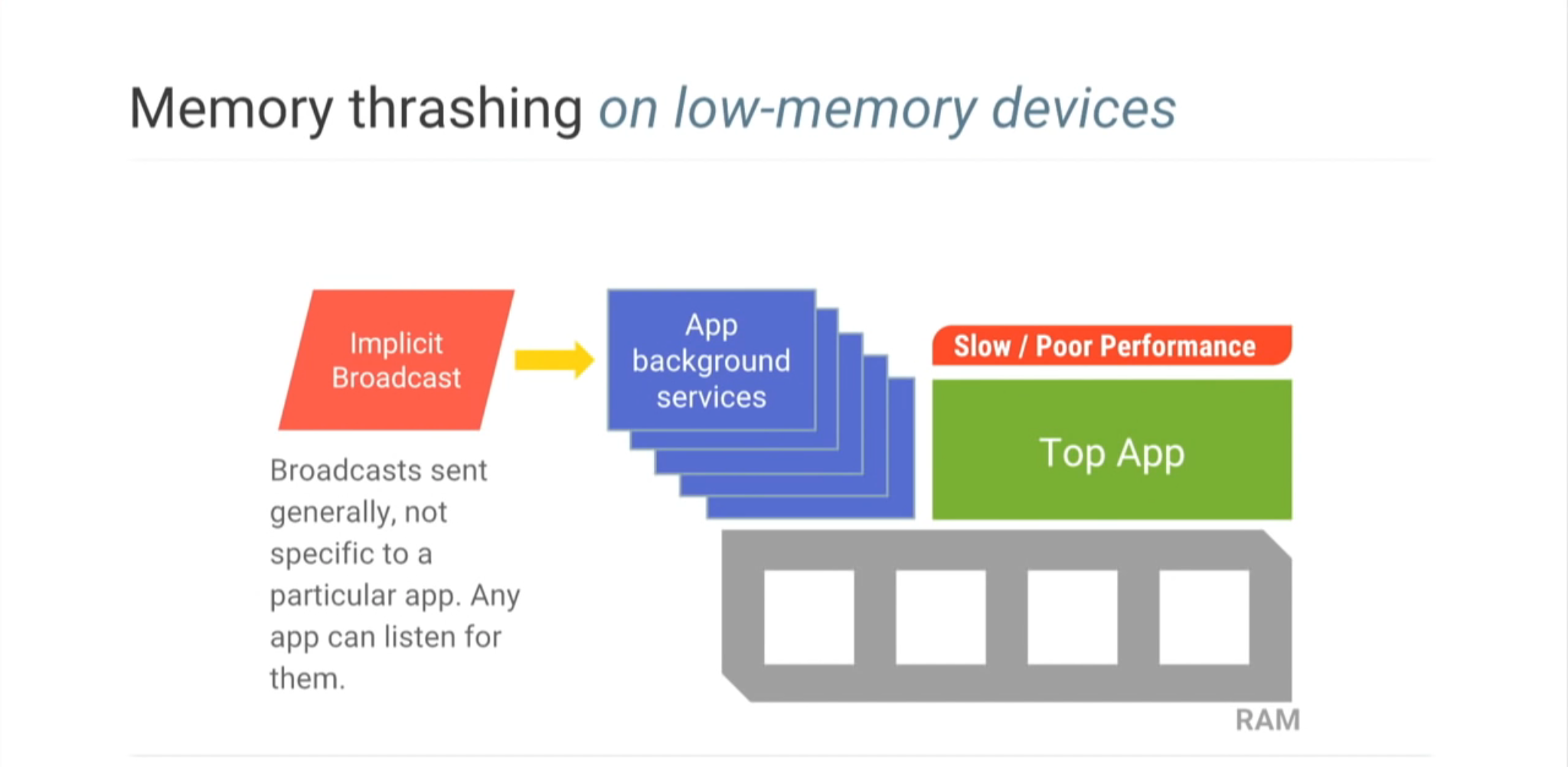

When the screen is on, background services also have an impact on memory. Such as you’re trying to take a picture with the camera, and you miss that moment because your phone was just too slow.

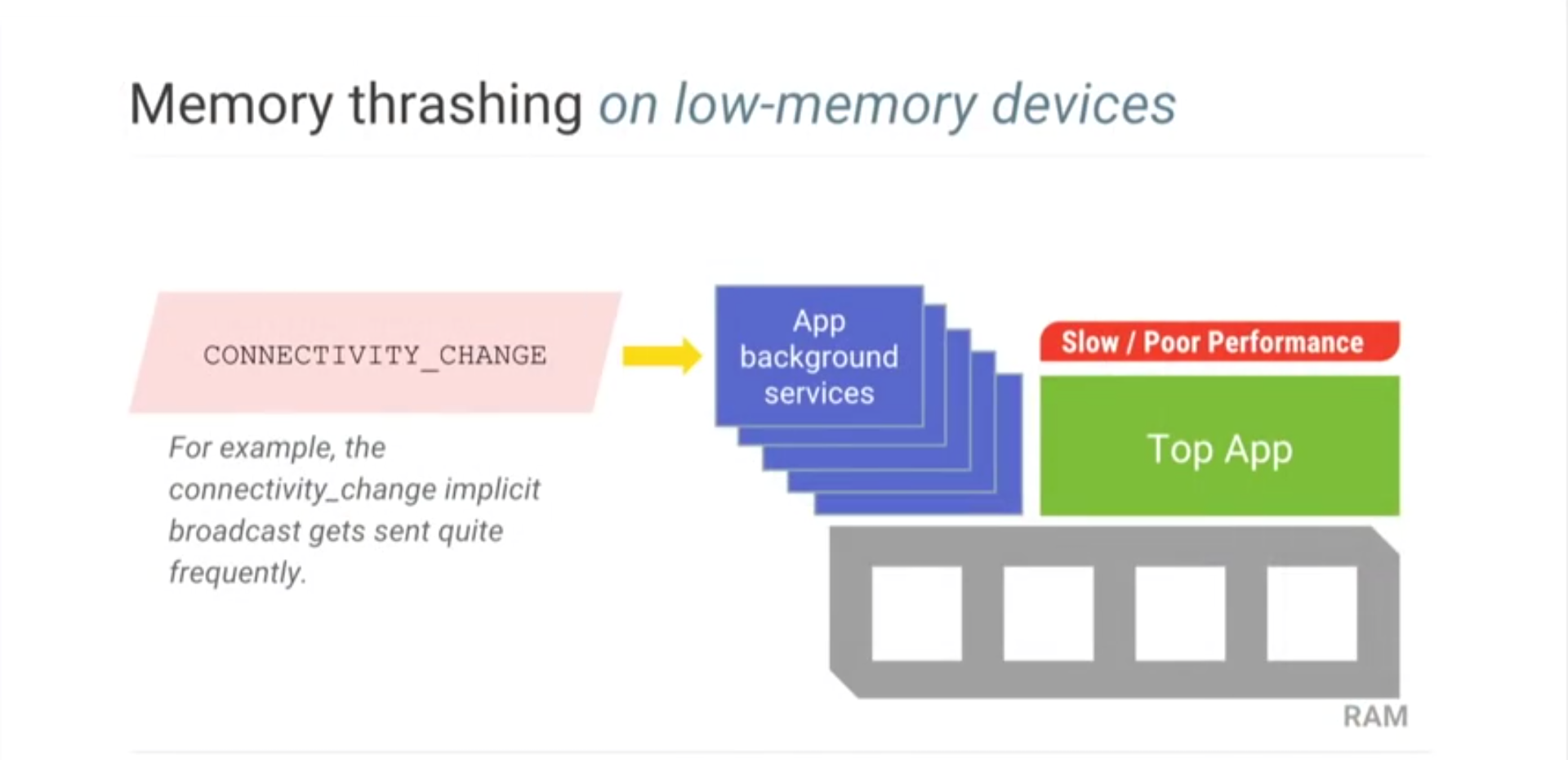

Now let’s reproduce this scene that you have an application which you’re trying to use, that’s the Top App here. At any given time, there’re a number of things happening in the background, lots of stuff happening in the background services. When a device enters a low memory situation, or if it just happens to be a low memory device, what happens is there’s no enough memory to run all that stuff in the background while you’re trying to use the device with that thing at the top. Well, at that point, Android is too busy trying to swap applications in and out of memory to let them do what they need to do in the background, which applies pressure on the application you’re actually trying to use. And the net result is that you get this frustrating, slow experience of the device.

Let’s figure out why background work is happening. One such trigger for background service is something called an implicit broadcast. A broadcast is just a signal that gets sent out on the device whenever something happens, the minute something changes. And the implicit type of broadcast is the type that gets sent to any app, or any applications can listen to it, versus the explicit side which would be something that gets sent to a specific application.

What makes this particularly bad is that often these broadcasts are listened to; the receivers for these broadcasts are declared in a static way in the application’s manifest file. What that means is that the application doesn’t actually have to be running for it to receive this broadcast and react to it. In fact, a broadcast sent in this manner would cause the applications that are not even running, but listening for it, to be woken up, brought into memory, and react to it in some way. And while Android is too busy doing that, the application that you’re actually trying to use starts to be sluggish and slow.

2.2 Memory Thrashing & Optimizations

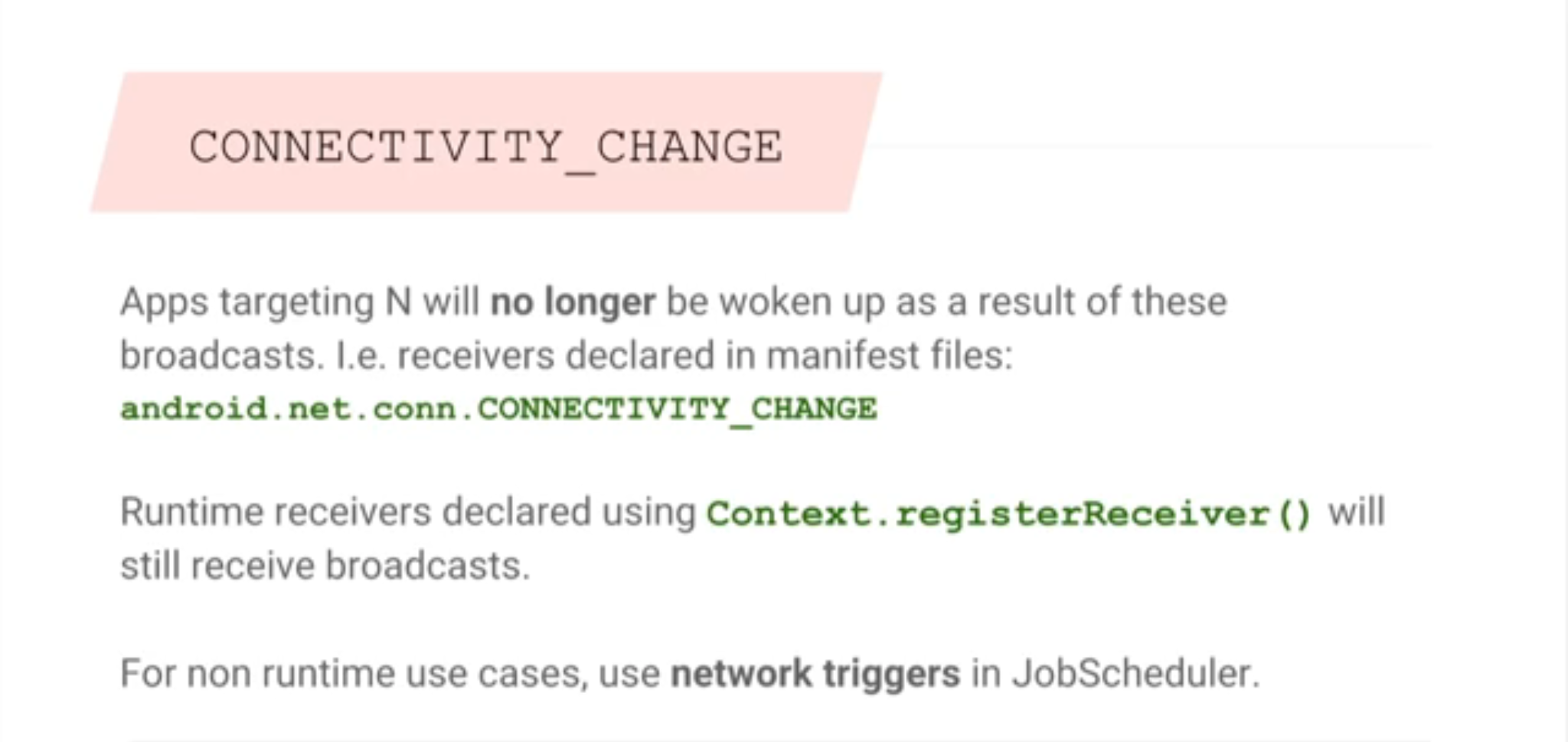

A broadcast called CONNECTIVITY_CHANGED which gets sent quite frequently on your device. Any time you switch from Wi-Fi to cell, or back or any kind of connectivity change happens, this broadcast gets sent.

And it turns out a lot of applications listen to this broadcast in a static way, by declaring receivers in the manifest file. And so, whenever this broadcast gets sent, lots and lots of applications are wakening up to perform activity in the background. And you get a frustrating experience on your device.

How to solve it?

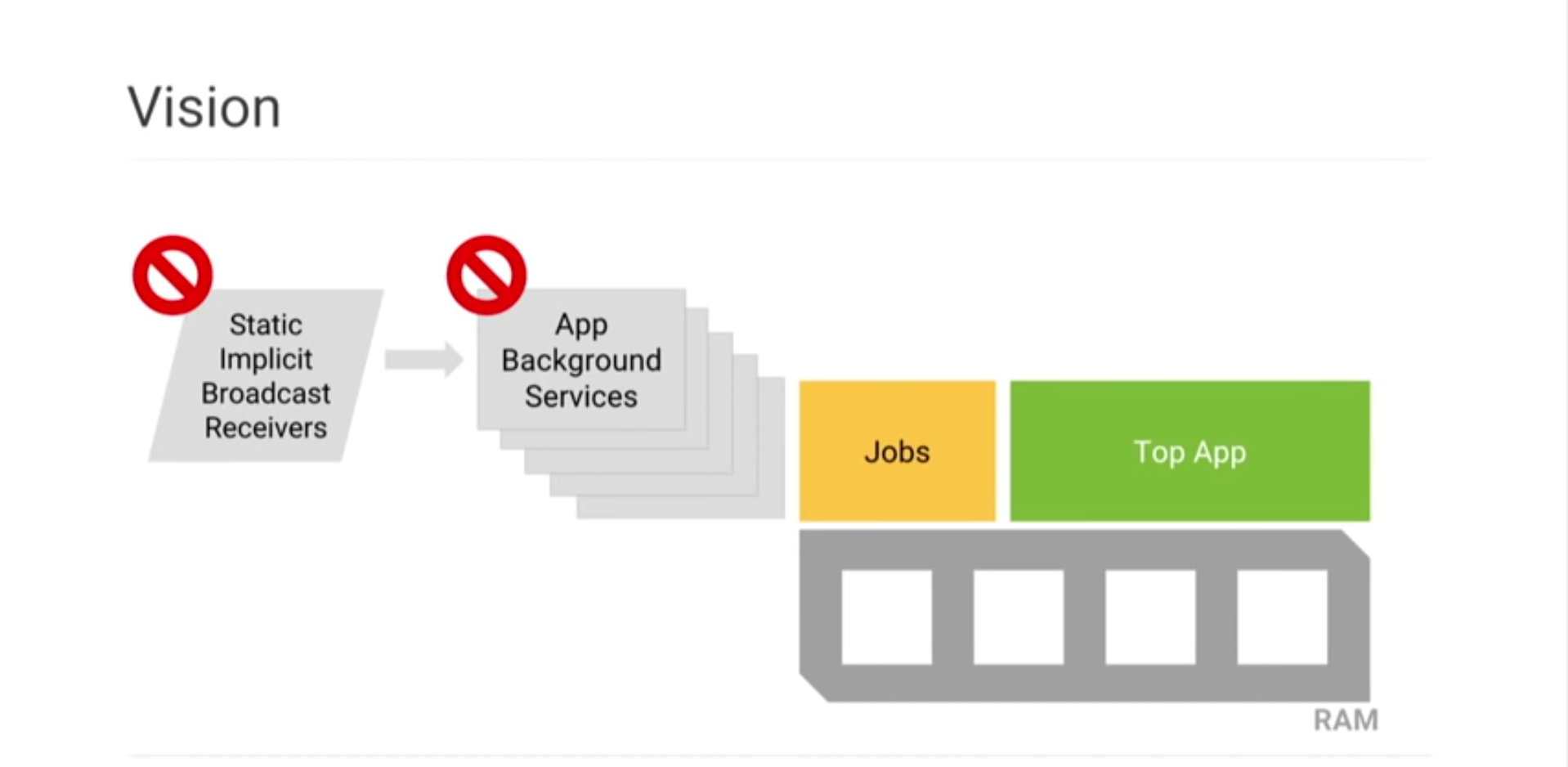

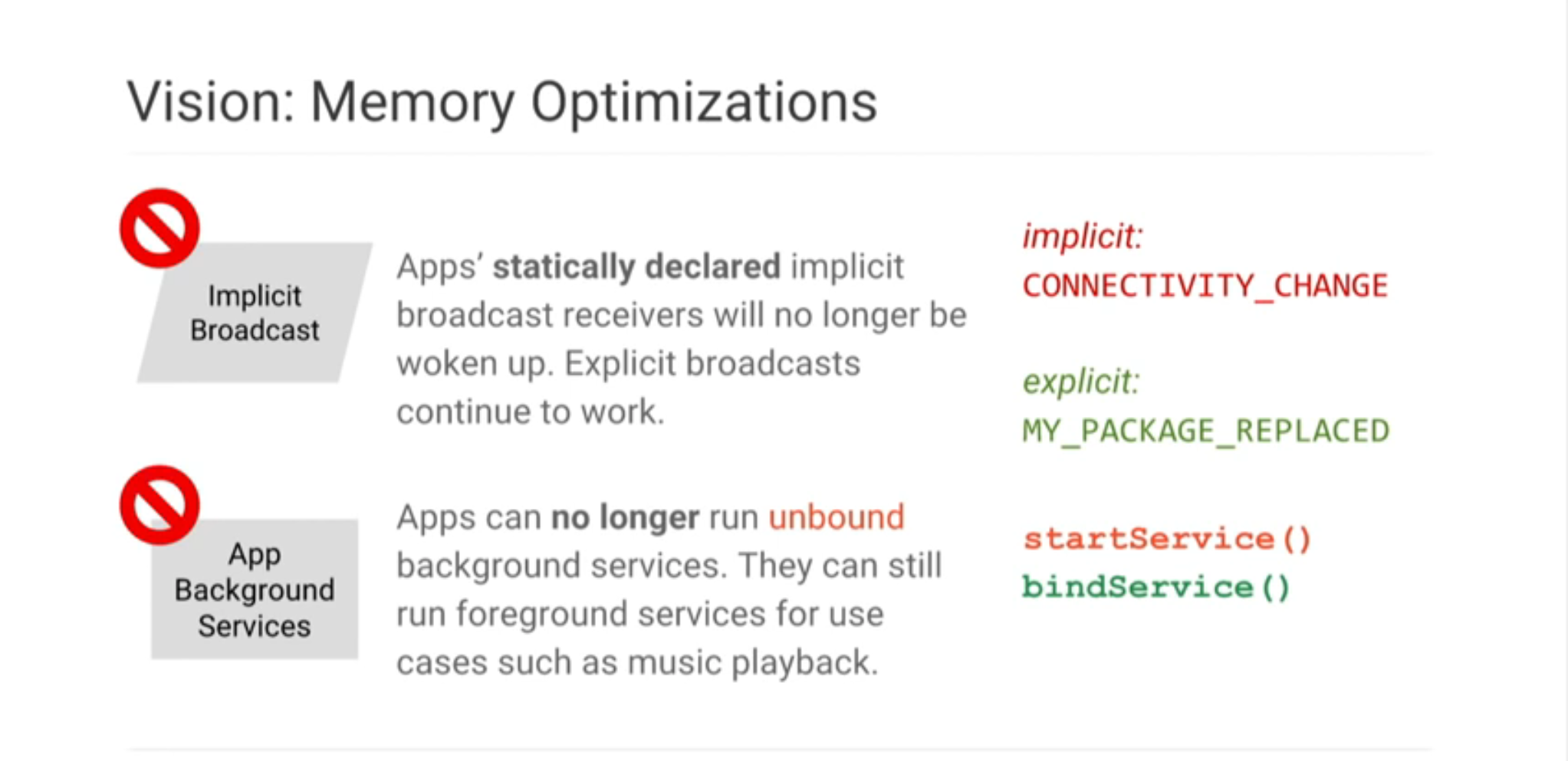

We envision that applications perform any background activity using exclusively JobScheduler jobs. And they reduce their reliance on background services and statically declared receivers for implicit broadcasts.

It means the applications’ statically declared implicit broadcast receivers would no longer get woken up. One time declared receivers would continue to work. Explicit broadcast receivers would continue to work, both declared statically or at one time. But the statically declared implicit broadcast receivers would be the ones that are specifically affected.

Second, for background services, Google envision that apps are no longer running background services or dependent on that for any kind of background execution. But background execution is important, and for that, developers can use JobScheduler or Jobs. Now, foreground services will still continue to work

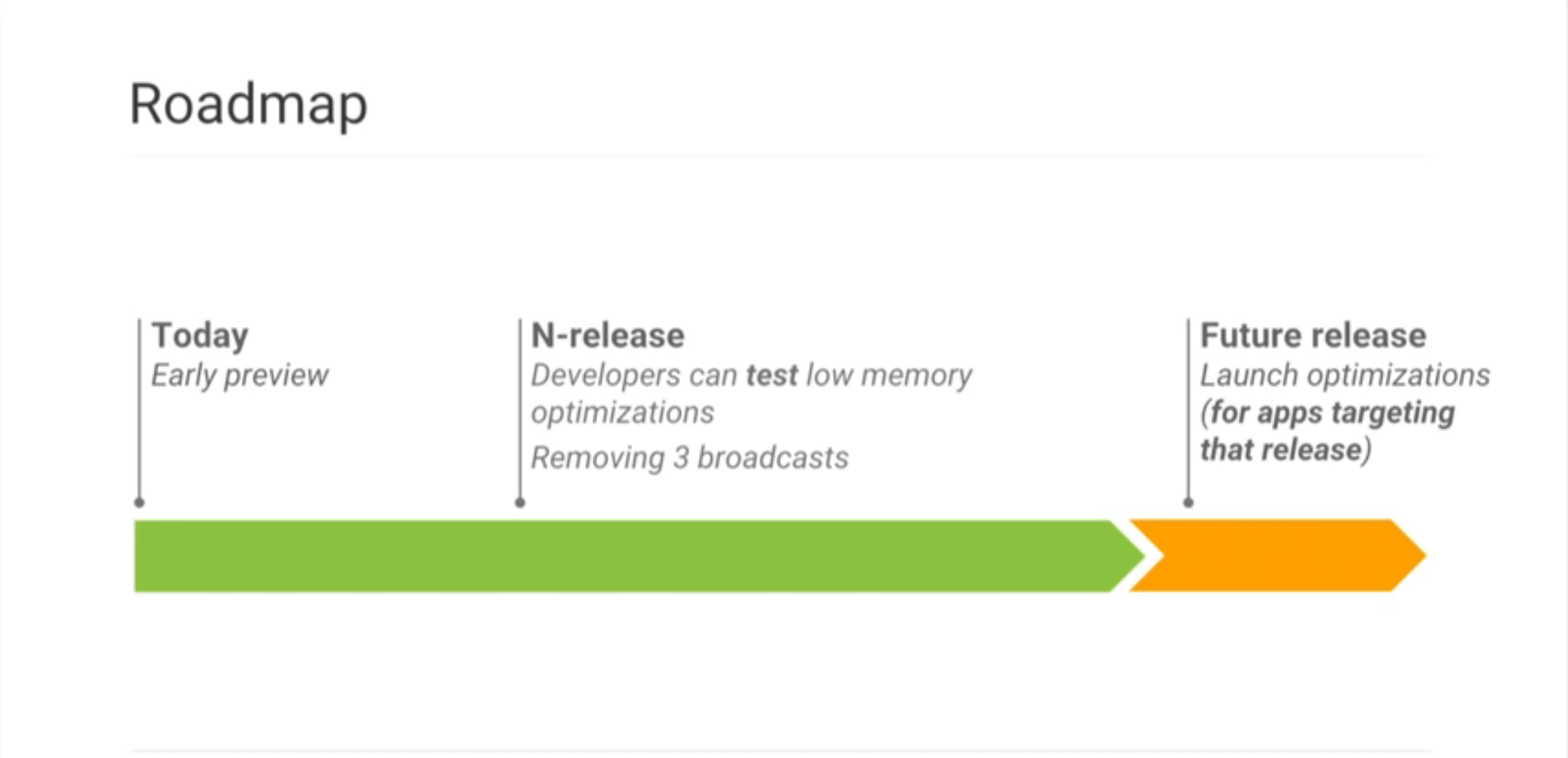

And this envision is for future of Android, and this is going to be ready in some future release. And they’ll apply to the apps that target that release.

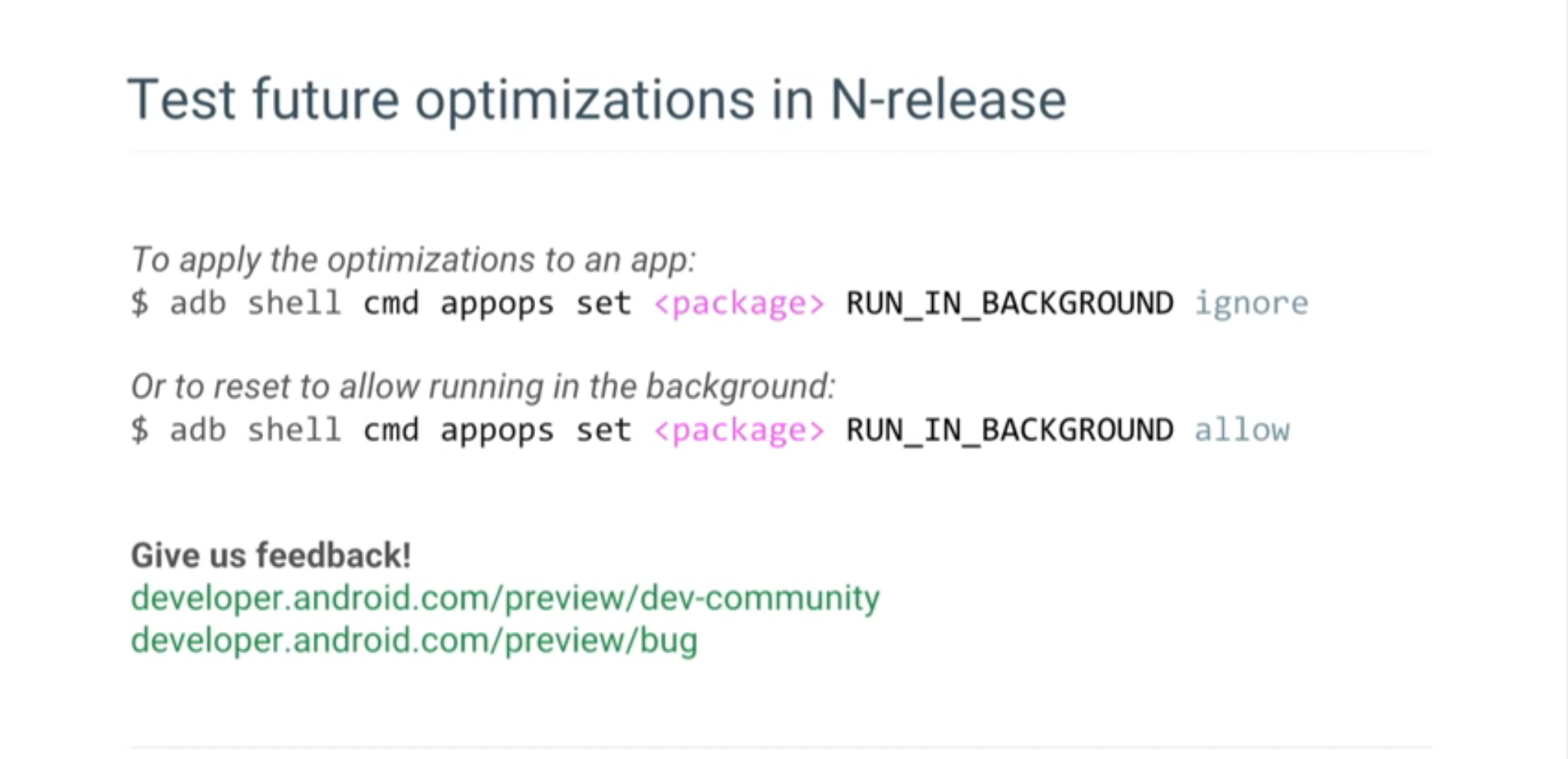

Use some adb commands today in the preview and apply them to your application, and starts testing to see what happen under these conditions.

2.3 Memory thrashing: CONNECTIVITY_CHANGED

Applications that are targeting N-release will no longer be woken up as a result of this broadcast. This means that if you’ve declared a receiver for this broadcast in your manifest file, that’s no longer going to work.

If you declare it at runtime, runtime time receiver for broadcast will continue to work because your applications are already running at that point. And for other use cases, you can use JobScheduler. And JobScheduler already has network trigger semantics.

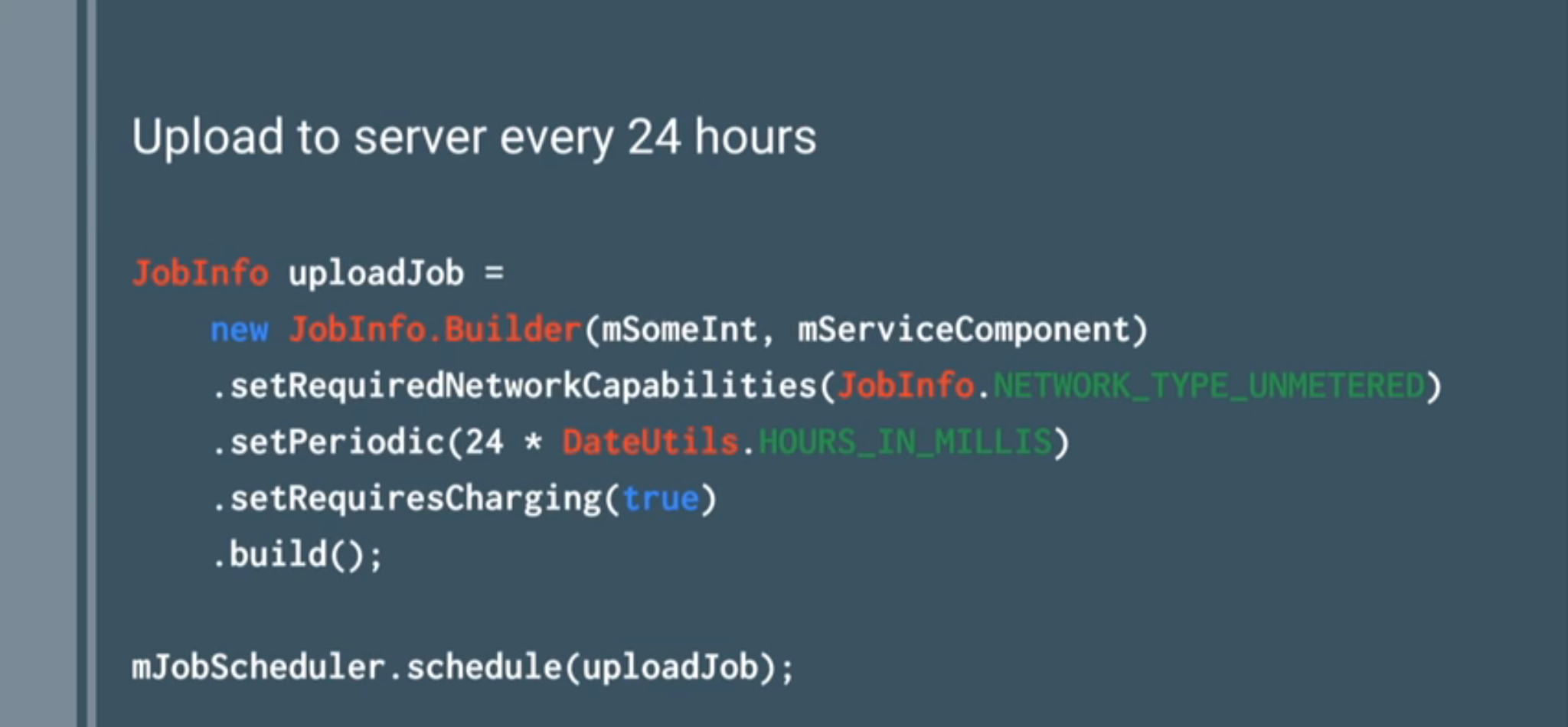

First of all, create an object using a builder. You can specify a required network capability to be that of network type Unmetered what that typically translates to is a network that doesn’t cost the user money, and most Wi-Fi networks fall into that category. So in a way, you’re specifying the Wi-Fi connectivity here. Second, define your job to sync up with cloud backend server every 24 hours, note that it doesn’t have to be by the hour, in other words, set up a periodicity of 24 hours; Then consider your do this when the device is on charger, so you specify the set requires charging constraint. And those four lines, you can schedule a job and it’s done.

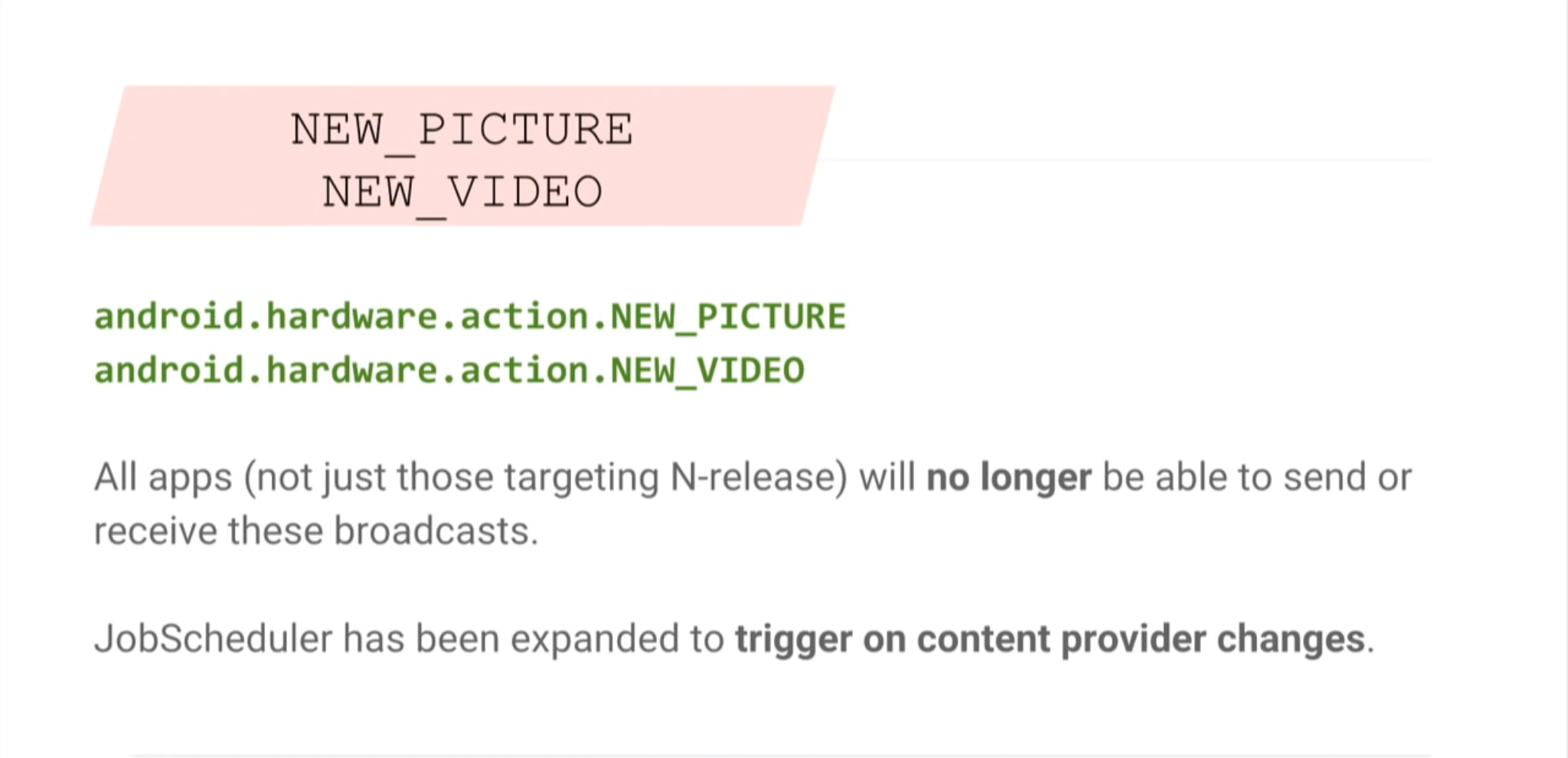

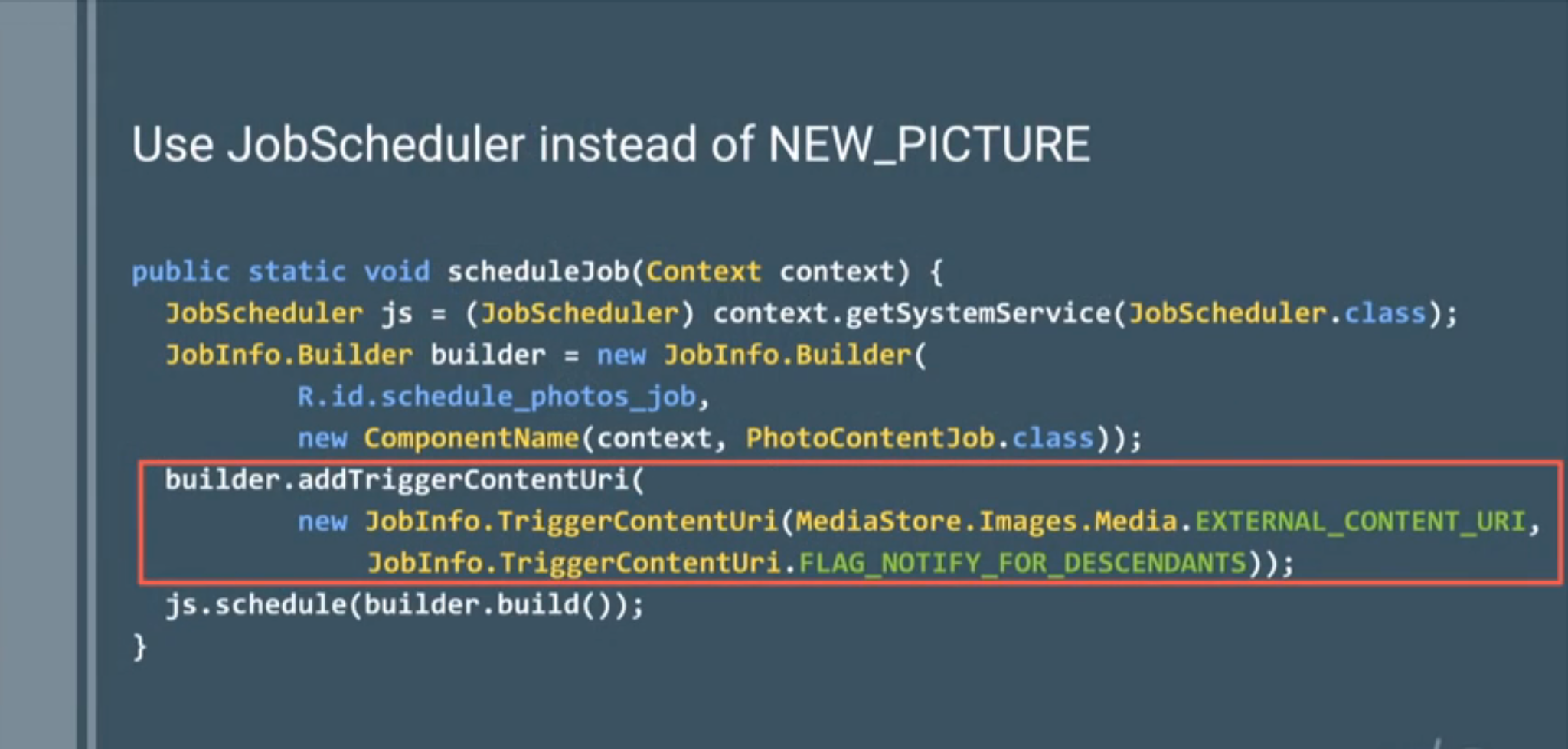

2.4 Memory thrashing: NEW_PICTURE, NEW_VIDEO

The other two are NEW_PCITURE and NEW_VIDEO. These are two more implicit broadcasts that are sent right when the user takes a picture. And they’re sent by the camera. And that’s sort of the worst time when you want a lot of other background stuff to be happening because you want to focus on taking that next picture, or whatever it is you’re doing with the camera application.

So starting with the N-release, all applications will no longer be able to send or receive two broadcasts, so not just those targeting N, all applications.

And in fact, these broadcasts are actually pretty important because they unleash some pretty cool use cases; one of them is uploading photos. As soon as you take a photo, you want that uploaded, but maybe you can wait for JobScheduler to be triggered on context provider changes. So the media folder has a content provider URI that could be the trigger whenever something updates there to upload that photo.

Because you’re using JobScheduler, system can optimize when that action takes place. It doesn’t have to happen immediately when you’re trying to take that next picture. It can find the next opportune time to do it, depending on the memory conditions.

You get an instance of JobScheduler service, create a builder object, and specify constraints on the network type and the periodicity, and add a trigger for a Content Uri update for NEW_PICTURE. And last you can schedule your job now.

Note: More information you can get in the Android Developers website: https://developer.android.com/preview/features/background-optimization.html;

3 APIs & Diagnostic tools

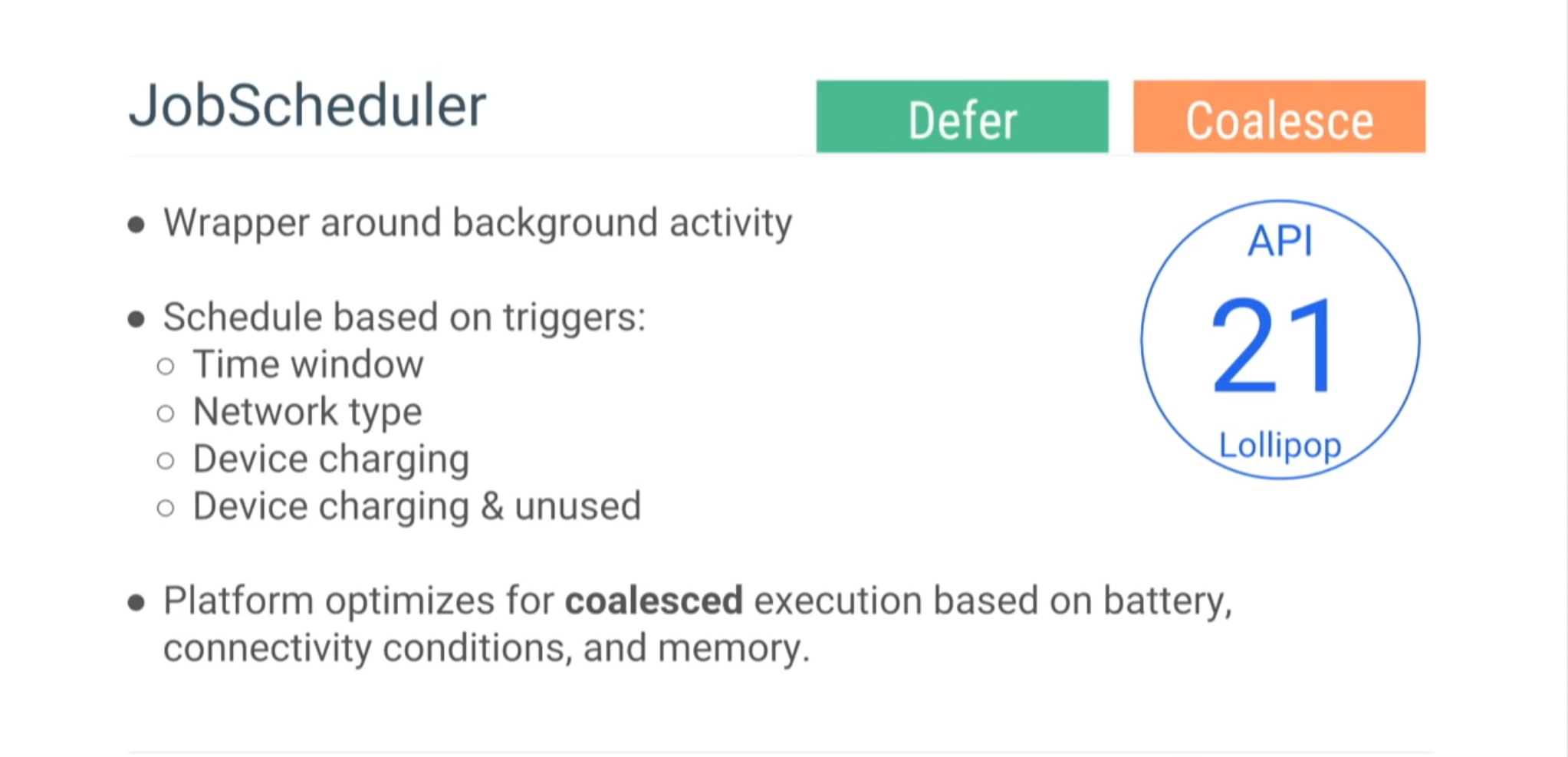

3.1 JobScheduler

The JobScheduler is just like a wrapper around any background activity, so any background sync, any background activity that you have; JobScheduler is the way to think about scheduling those.

And this is slightly a paradigm shift, where what you’re doing is you’re letting Android know that I have some tasks that need to get done, and you specify certain triggers when Android will schedule those jobs for you, rather than something you try and take care of yourself.

These triggers, when you request Android to schedule your job, could be used on a certain time window. It means that you have a job that’s important, not exactly urgent, and it doesn’t need to happen right away, you can schedule this job any time within the next one hour. And what Android would do is once many applications are using the JobScheduler API, it now has this context about all the background activity from the different apps that needs to happen, and it’s going to do a good job at scheduling your job at just the right time, so that the efficiency of the CPU and the networking radios can be maximized.

Now what you can also do is specify triggers based on network connectivity or the type of network that becomes available. For example, an application that’s uploading a whole bunch of photos or videos that you might have on your phone can schedule or specify a trigger for of Wi-Fi network, because Wi-Fi typically has more bandwidth less expensive in terms of money, and it costs also less power than cellular radio.

Also, you can tell that here’s a job that I want to get done and trigger it when the device is charging but not now. Because every time you plug in the device may not be the best time for all of the background jobs to start firing up. For example, you wake up in the morning and your phone is running low, and you find that power outlet. And plug in your device to get maybe 5 minutes of charge, right then if all of the photos and the videos that you took today start getting uploaded to the cloud, that’s going to be a not so pleasant experience for you. Because your device might get slow, but also you might not get enough charge out of the outlet cause you’re spending all of that energy. What you can do? Make sure device should be charging and relatively unused, Android smart enough to figure out when you are not actively engaged or interacting with your device, so it’ll wait a little while to make sure that this is a nice time to schedule all of those background jobs, and it will trigger your job right then.

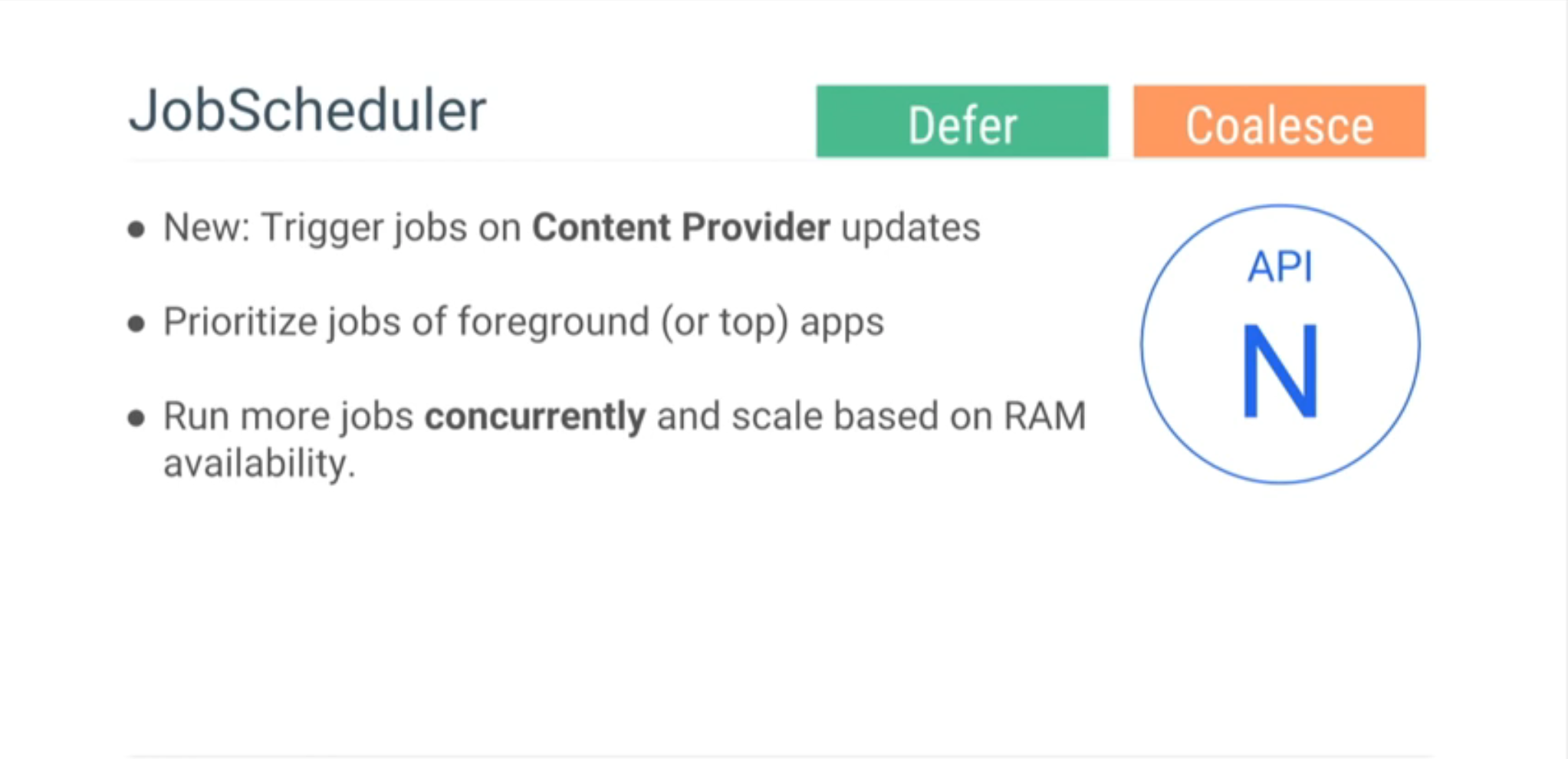

The below picture show the extension to the JobScheduler API in the N-release that is to take into account the memory conditions or the RAM conditions on your device.

So now JobScheduler also support to triggers based on content provider updates. And JobScheduler API is intelligent enough to prioritize all of the jobs for the processes or for the application that is in the foreground or that is running foreground service, to account for the fact that if you’re interacting with an app, all of the jobs for that particular app should get priority, an automatic priority or all of the other jobs that may not be as time critical. And finally, JobScheduler is aware of the available RAM on your device, so depending on how much RAM is available, it might choose to schedule more than one job at the time, or if the memory conditions are not ideal, or if you are running low on memory, then only a few jobs, or the top priority jobs will get scheduled first before all of the other ones get precedence.

3.2 Diagnostic Tool

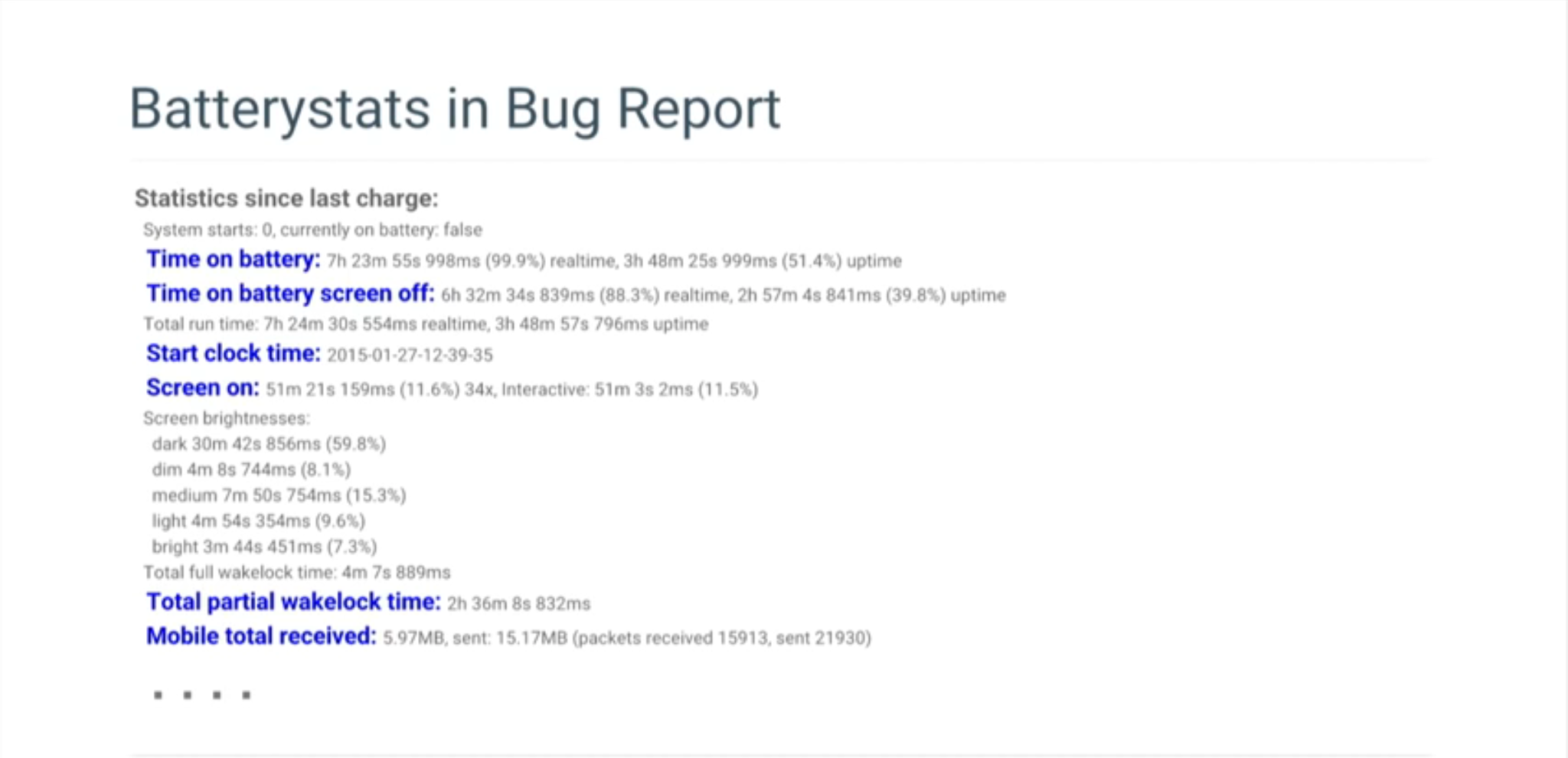

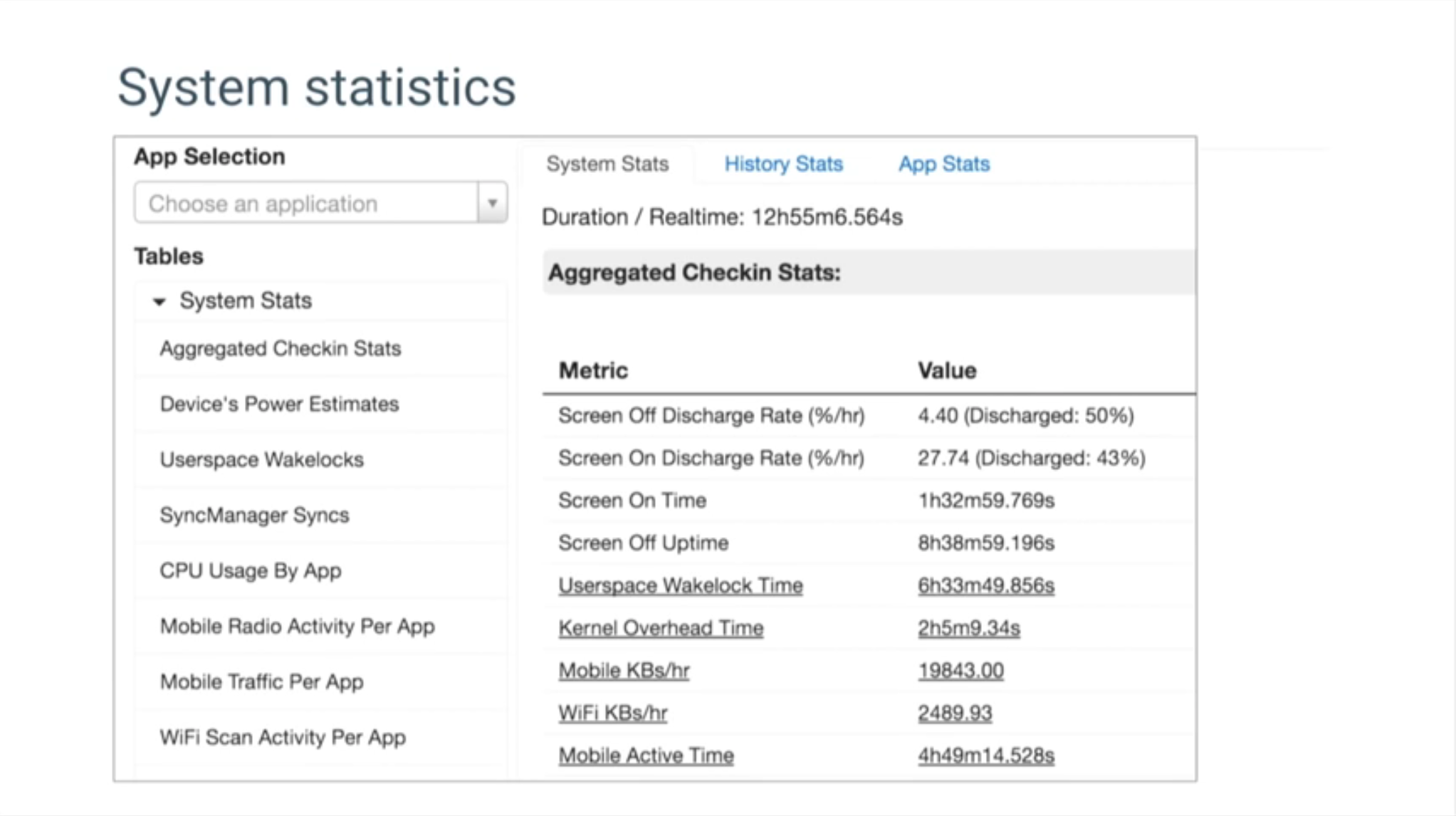

Now Android maintains data structure in memory on all the devices, and this log is called BatteryStats which is a set of cumulative counters that go on incrementing while your device is on battery, so since it’s in memory and these are cumulative counters that go on increasing, they need to get reset at some point when you’ve fully charged your device and you’ve just unplugged it.

For example, you charged your device overnight, and you unplugged it at 7 AM in the morning, maybe it’s about 10 and half hours since then. If you take a bug report on your device now, then it would contain the whole 10 and a half hours’ worth of Batterystats and counters about various things happening on your device that we think are relevant with respect to battery life. So things like how long was the partial Wakelock held on the device across all applications and on an application basis, or how much data was transferred over the mobile network or the Wi-Fi network, and what you can see here is there’s also a StartClock time which tells you exactly when the stats were reset. So this is really usefully when you’re trying to look at what all happened on your device that may have caused the battery to drain faster than what you would expect.

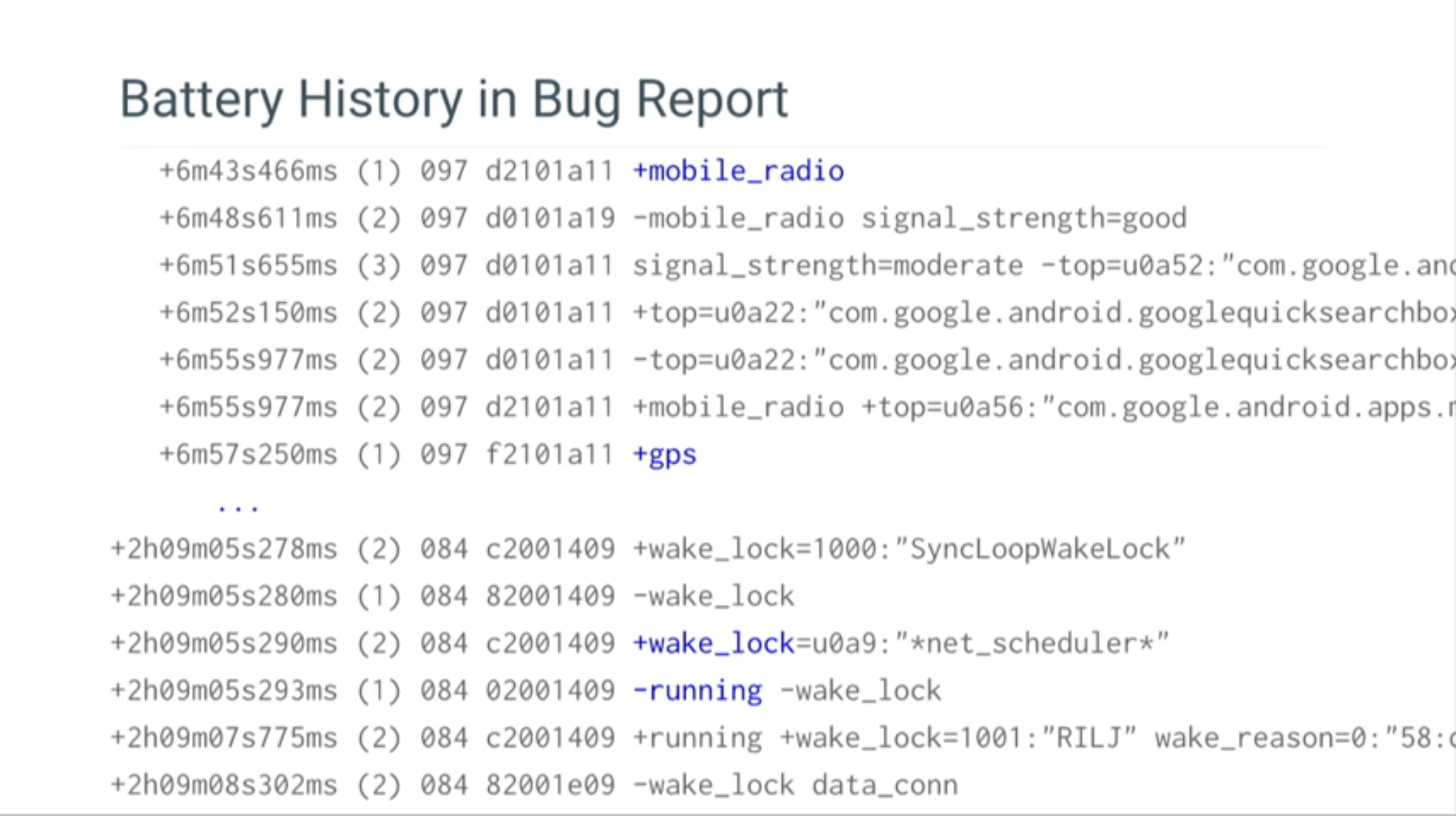

The other type of log that is present on the device is something that called Battery History, and what this is an event log of all of the state transitions for components on your device, or for actions like scheduling a wakelock, or an application scheduling a job, or the device going into suspend, coming out of suspend, or maybe it’s the network radio that got turned on. And this would contain an event log of a millisecond level granularity of everything that happened on your device since the state was reset.

So there is a tool can make sense of this entire thing, it’s called Battery Historian. It takes all of those logs that are present, the two logs that mentioned above which are present in the bug report, and it would help you look at them in a very intuitive and interactive UI that makes clear what the problem is on the device.

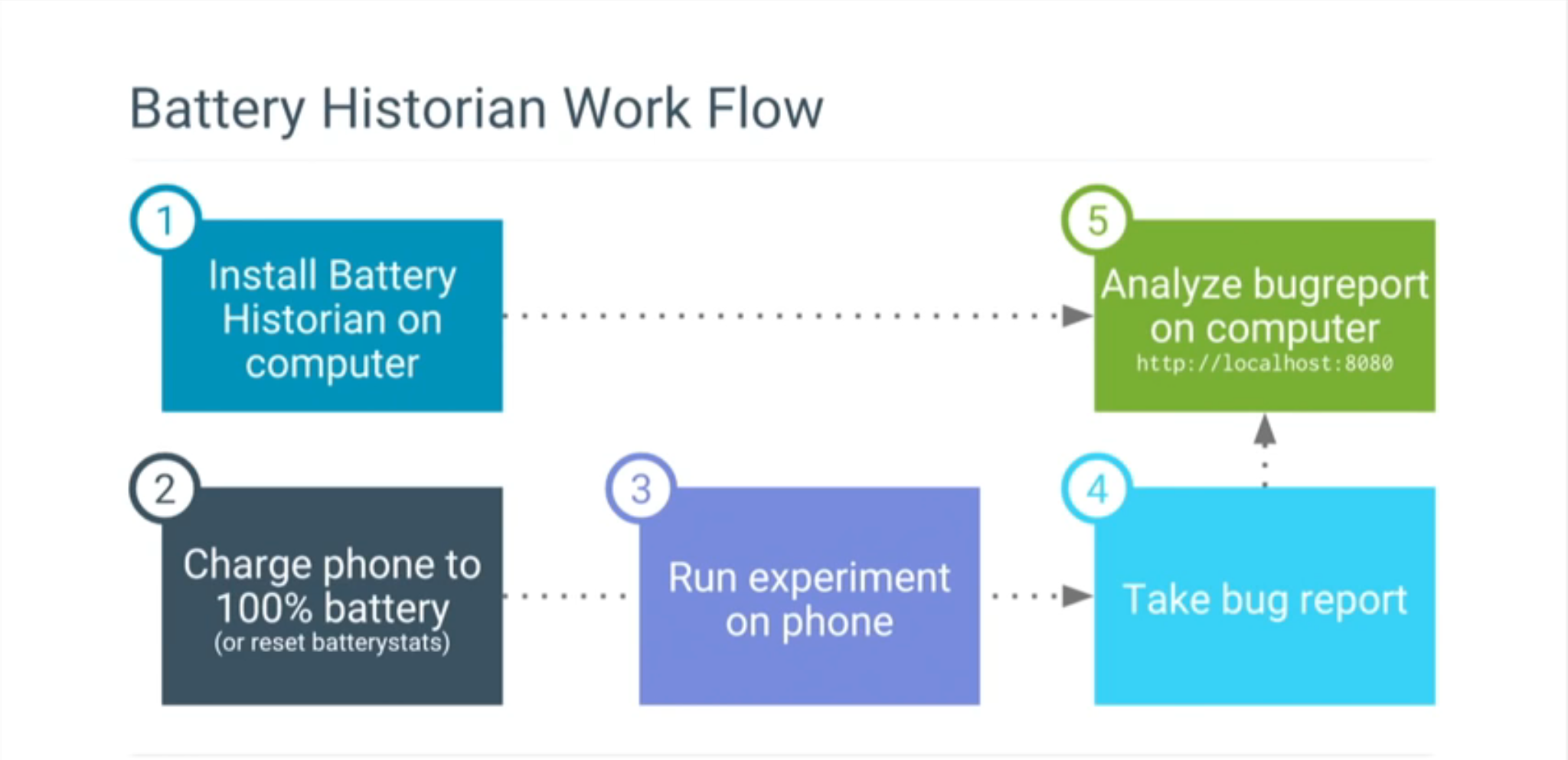

Let’s walk through the workflow of how this tool works.

Note: You can get this tool from github: github.com/google/battery-historian.

It is an open source tool available on GitHub ready for everybody to download. You can install it to your computer. Now you have your development device for the stats to be recent, because you want to have a good starting point, you can either charge the device up to 100% when the stats would get reset, or there is ADB command to actually manually reset the stats so you have a good initiation point. You can run your experience, it might last a few minutes, or maybe a couple of hours. And at the end of it, you take a bug report. And then, you upload that bug report on your computer that you have the Battery Historian tool.

- Basic Usage

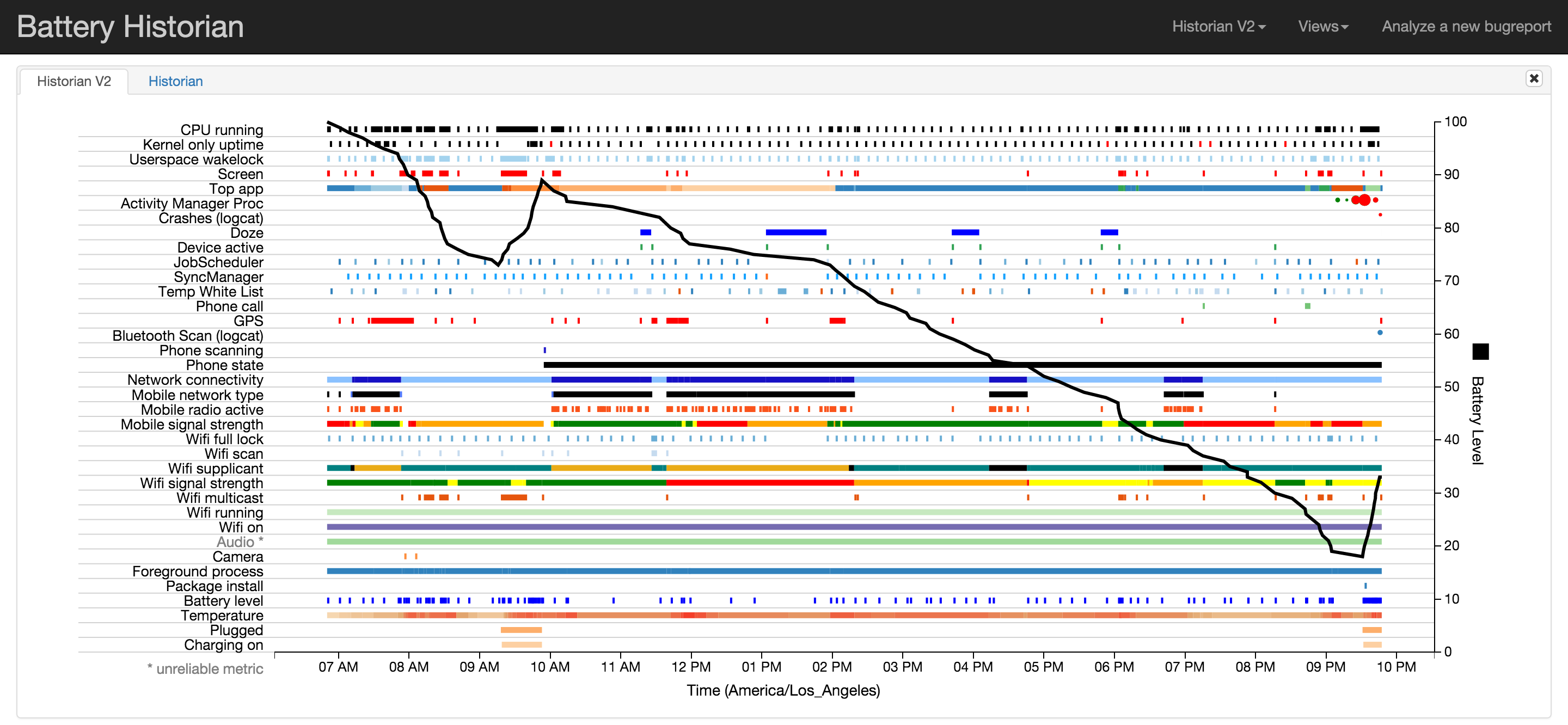

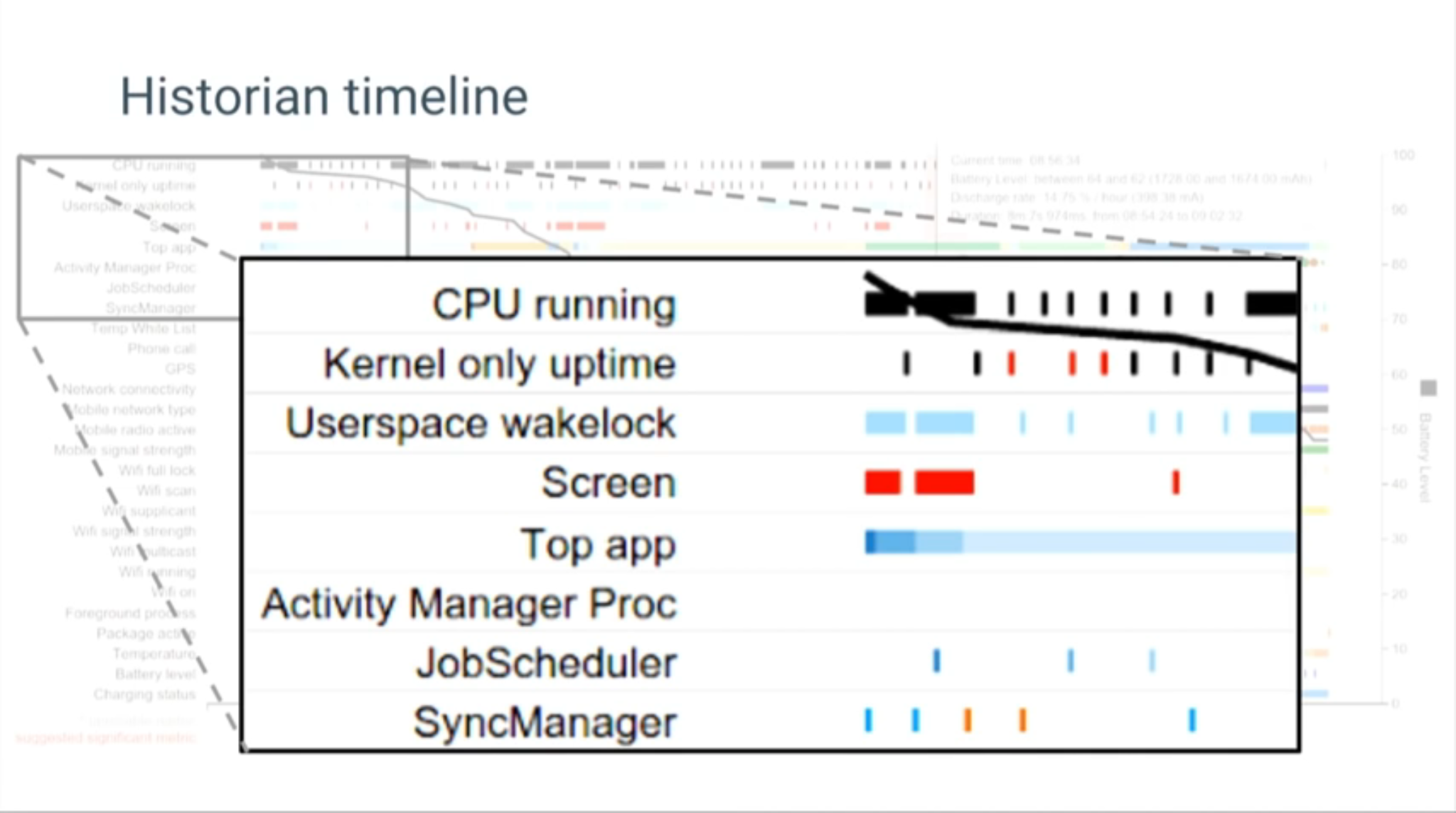

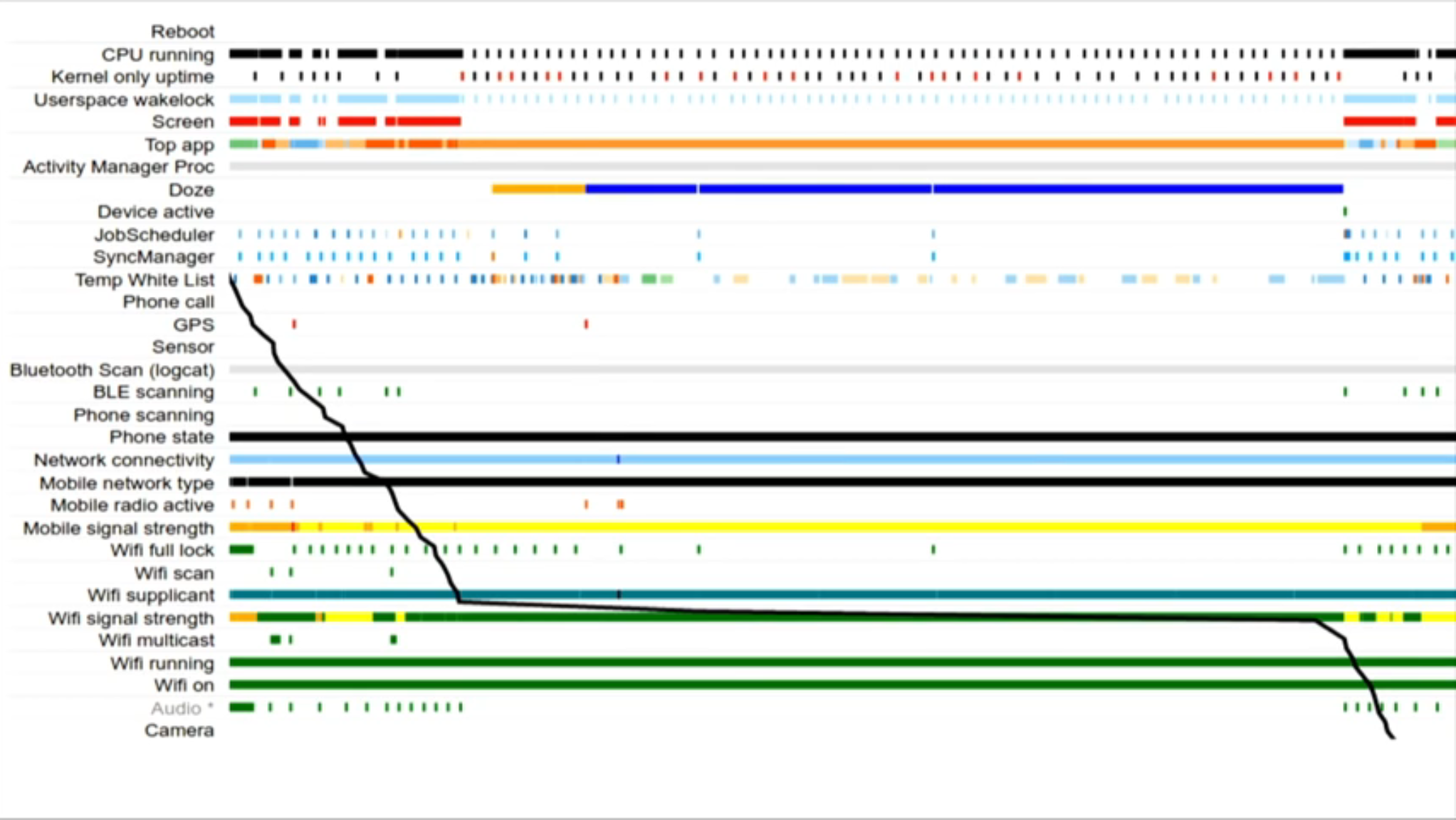

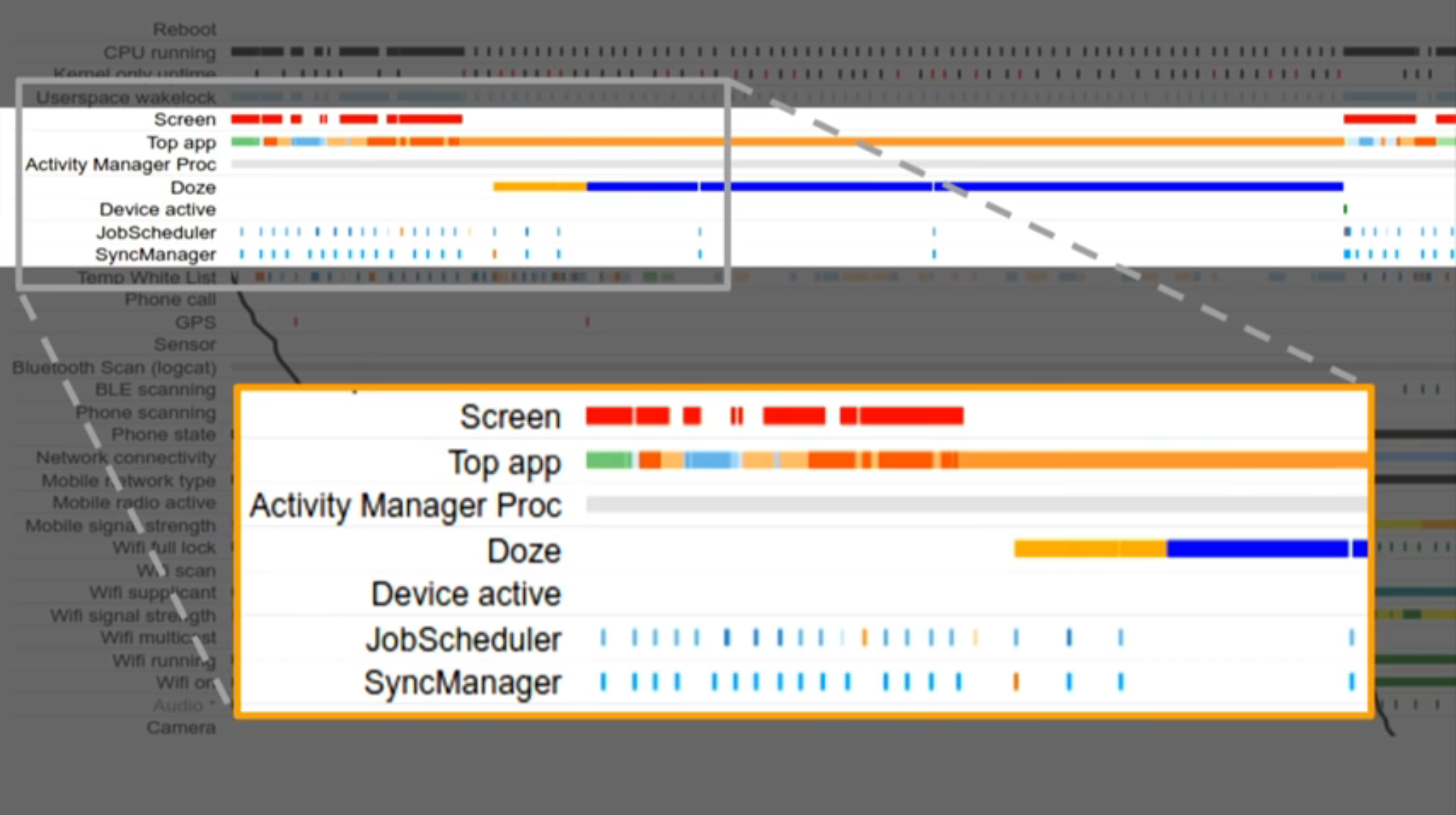

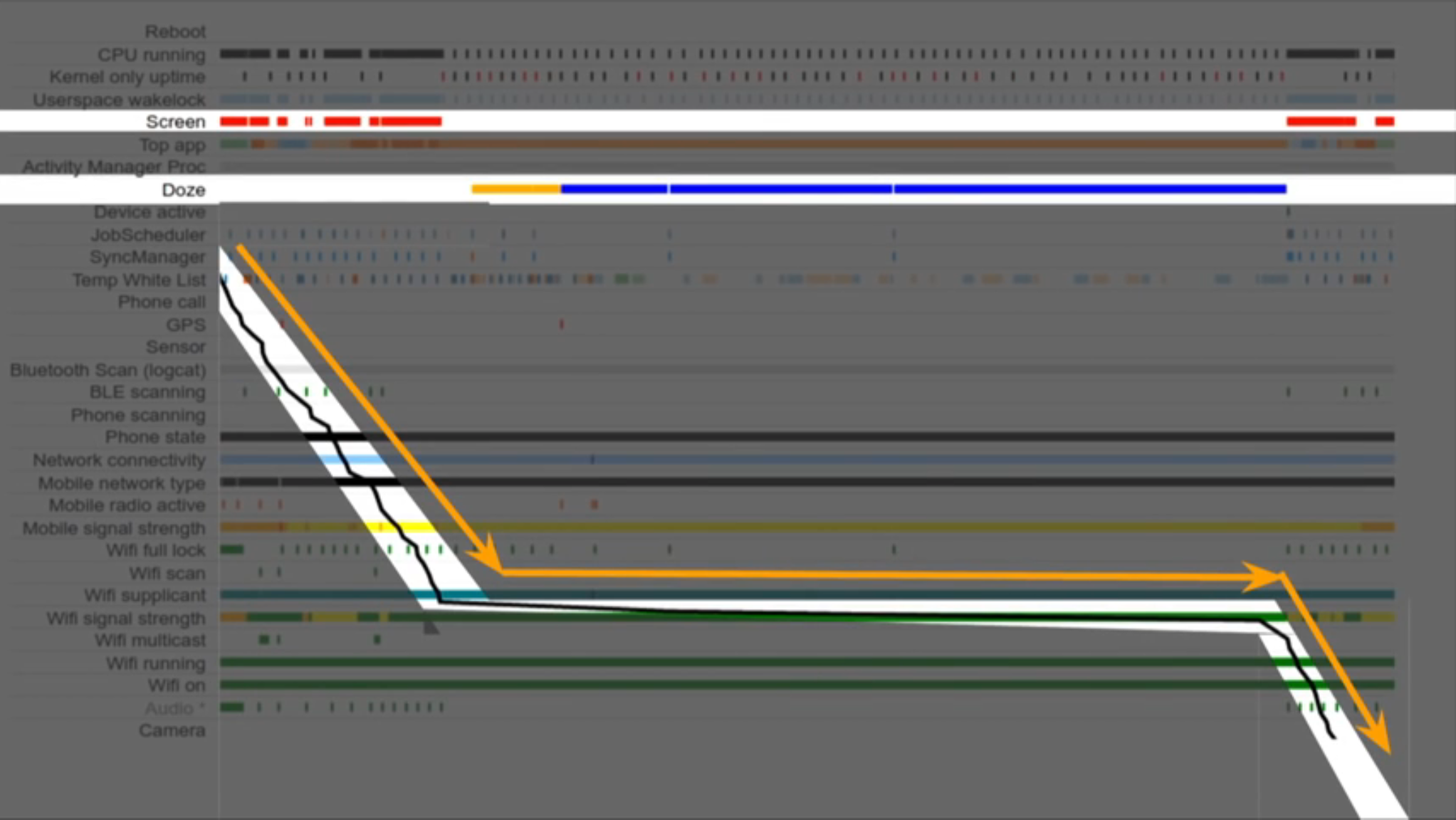

Let’s zoom into one of the rows, or a few of these rows.

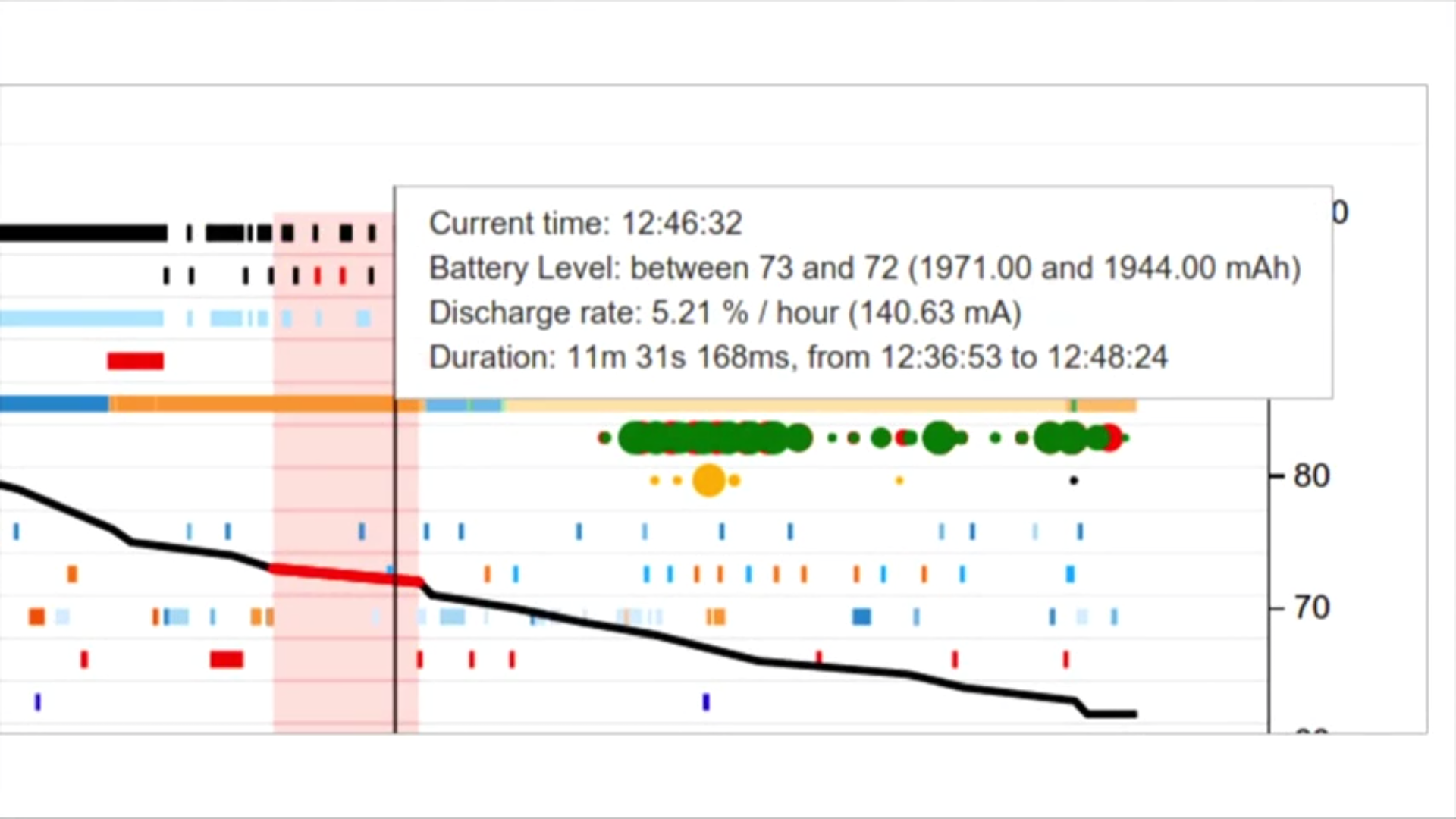

The top line which is CPU running, and what this indicates is it indicates is whether your device was in suspend or was it out of suspend. So the solid black bars are when your device was actually out of suspend and doing some activity. Similarly, you can see things like when was Userspace Wakelock held or when the screen was on. And the information about any of your jobs or syncs will also appear here. And in this UI, you can zoom in to every little event that you see, no matter how long. And if you take your cursor over that, it will show you a nice tutor.

So for example, at this point in the UI we zoom in, and it tells me exactly what the current time was at this instance. And the red highlighted portion now shows you the battery level drop from 73 to 72 and how long it took for the device to discharge from 73 to 72, giving you an indication of what the average discharge rate was during that time. And you can see all of the events lined up nicely, so you can actually figure out your device were discharging rather fast, what were the events that were happening on the device.

- Use case for JobScheduler

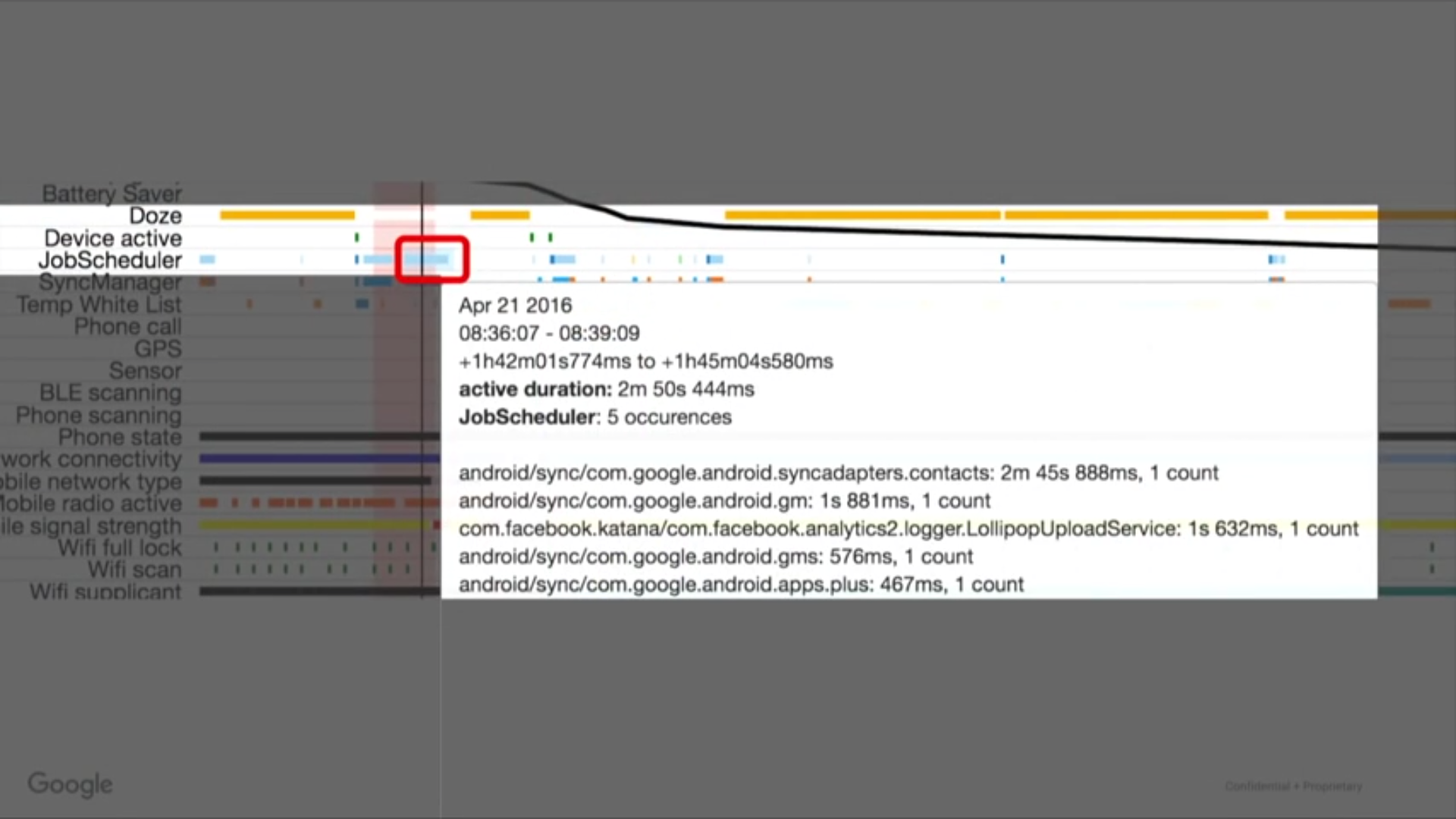

If you have adapted or migrated your app to start using JobScheduler now, how do you figure out when your jobs are getting scheduled.

So in the JobScheduler row, you go on any one of those events, and if you are in a zoomed out view, it might collapse a bunch of these little jobs that didn’t last as long. But it will give you information about how many jobs were run in that particular small box and for how long each of those jobs ran. And you can zoom in if you like.

- Use case for Doze mode

Here is a bug report about Doze issue, and the black line that you see going down that’s not exactly horizontal, that’s your instantaneous battery level. So typically, it would start off with something high if you started with 100%. In this case, it’s manually reset the stats, so it starts somewhere around 50%. And then let’s zoom into this little area.

When you screen is on, you can see that the frequency of your jobs and syncs was fairly high. All of the jobs and syncs were getting scheduled fairly periodically. But then, after the screen has been turned off for a while, what you can see in the Doze line or the Doze row in orange, that’s the lighter version of Doze kicking in. So some applications would lose network access. And you start to see that now your jobs and your syncs are beginning to get less and less frequent, and they’re getting batched together. And further out, after the device has had its screen off for a while, and it has been stationary, you see the device entering this deeper Doze mode which is shown in the blue row here, and when that happens, the device is not being touched by the user, is not being used, and that’s an opportunity for the JobScheduler API to start throttling and batching together a lot of activity. So you see that under blue bars, the JobScheduler and the SyncManager frequency is fairly infrequent, and they get scheduled during the maintenance windows.

And this slide will help you get a perspective on what uses the most power on your phones. Initially when the screen was on, battery level was lost very fast just like slope of the line, that’s the battery level going from 50 to maybe 30 very quickly. And after the screen has been turned off and the Doze mode has kicked in, battery is not declining as fast, and it might have even lasted a couple of hours in that state without discharging a whole lots of battery. And then towards the end, as soon as screen is turned back on, the device exited the Doze mode, and you go back to that steep discharge of when you’re actually playing a game or watching a video.

- Use case for System Statistics

And the same tool will now show you all of this information that was collected on the device, so which jobs were run, for how long they were run, which application required Wakelocks, and for how long they did. And in general, for the entire device, there’s a whole bunch of information here, such as the mobile radio activity, which application used the most amount of mobile traffic or Wi-Fi, number of Wi-Fi scans.

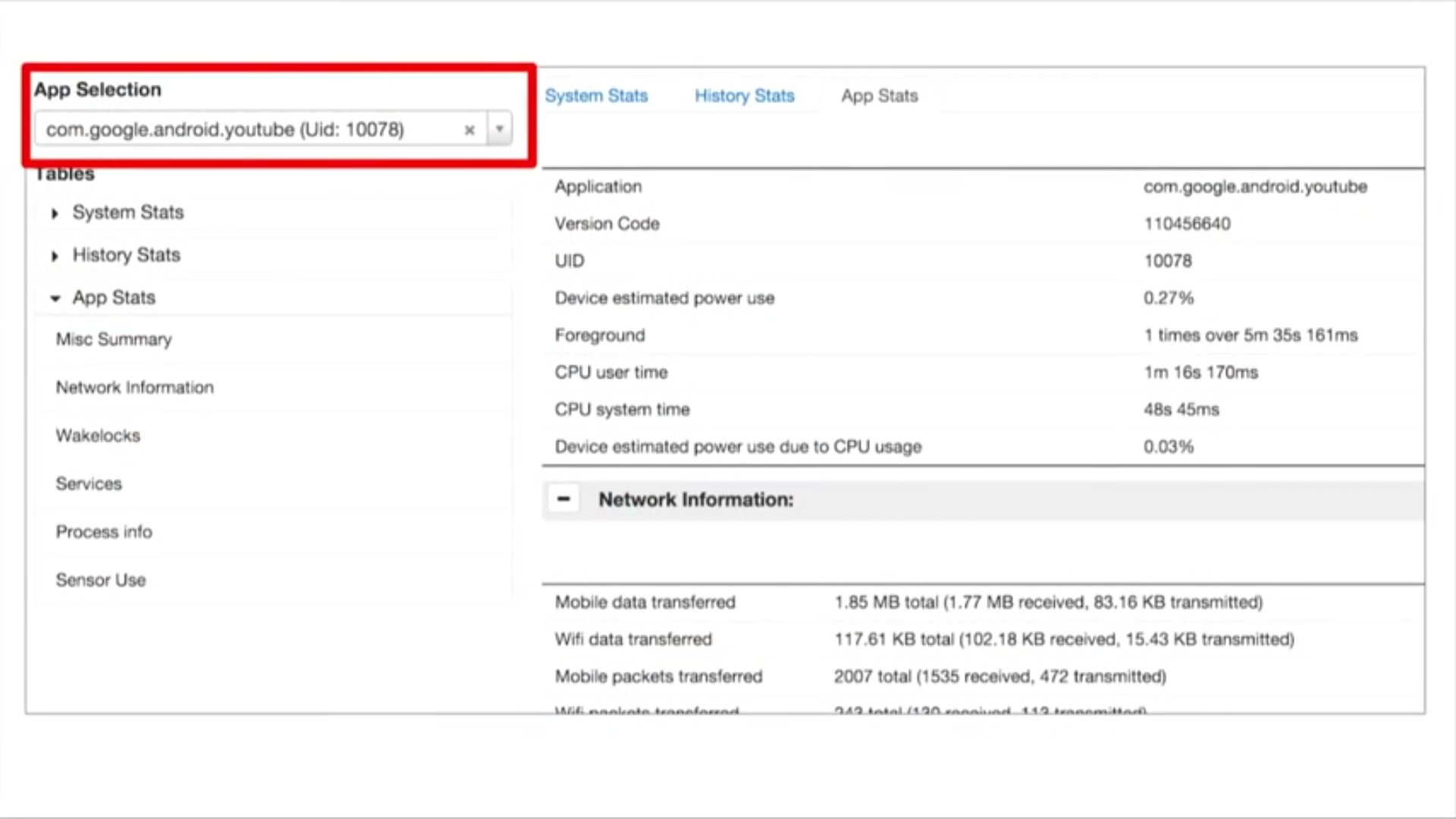

- Use case for Application

There is a App Selection bar here, an you can actually search for and pick up each app, and the moment you’ve done that, you get taken to this App Stats view which tells all of this same information just for this app, so you can look at all the jobs that got fired, what all processes you were running, how much mobile data, or Wi-Fi data, sensors, all the good stuff just there for this app. Once you’ve picked a application, if you go back and look to the UI of the timeline of events, you will see that in the job row, or the JobScheduler row, or the Sync row, only the jobs and syncs for this application will appear, and all else will disappear.

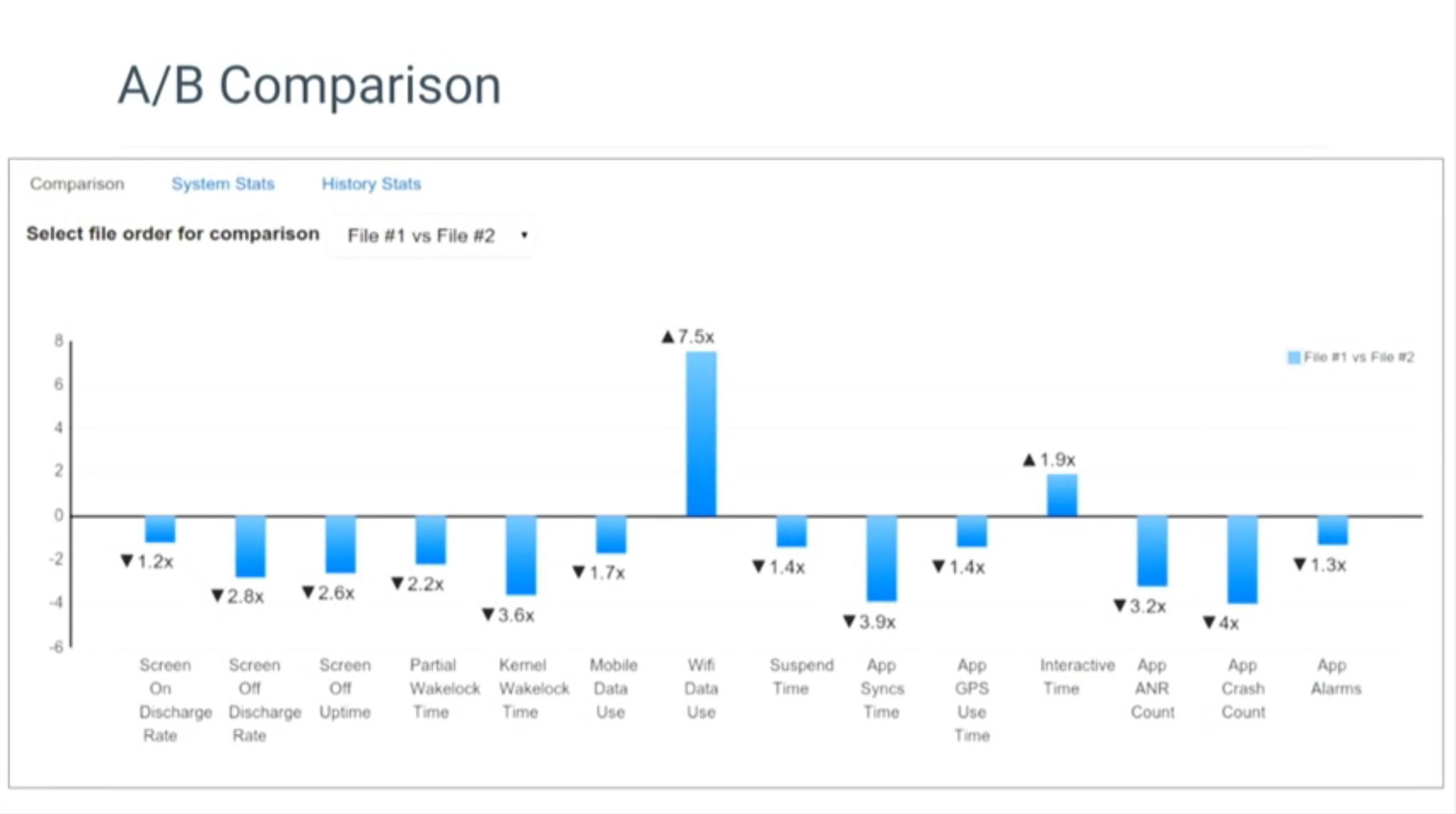

- Use case for A/B comparison

You can upload two bug reports, and if you have a good case and a bad case, then what the tool will let you do is it will highlight all the biggest differences that it sees between these two bug reports.

For example, it’s comparing now file1 versus file 2, and it shows that in file 1 it has used 7.5 times more Wi-Fi data than the others. And the screen off discharge rate on the first one was less than 2.5 times, and whole lot of other good stuff. If you upload two bug report, it automatically normalize those two bug reports, so if you have on bug report that was taken for four hours, and the other that was at two, it will automatically normalize all of that, and show you a good comparison which can give you a very good starting point as to what actually changed on the device.

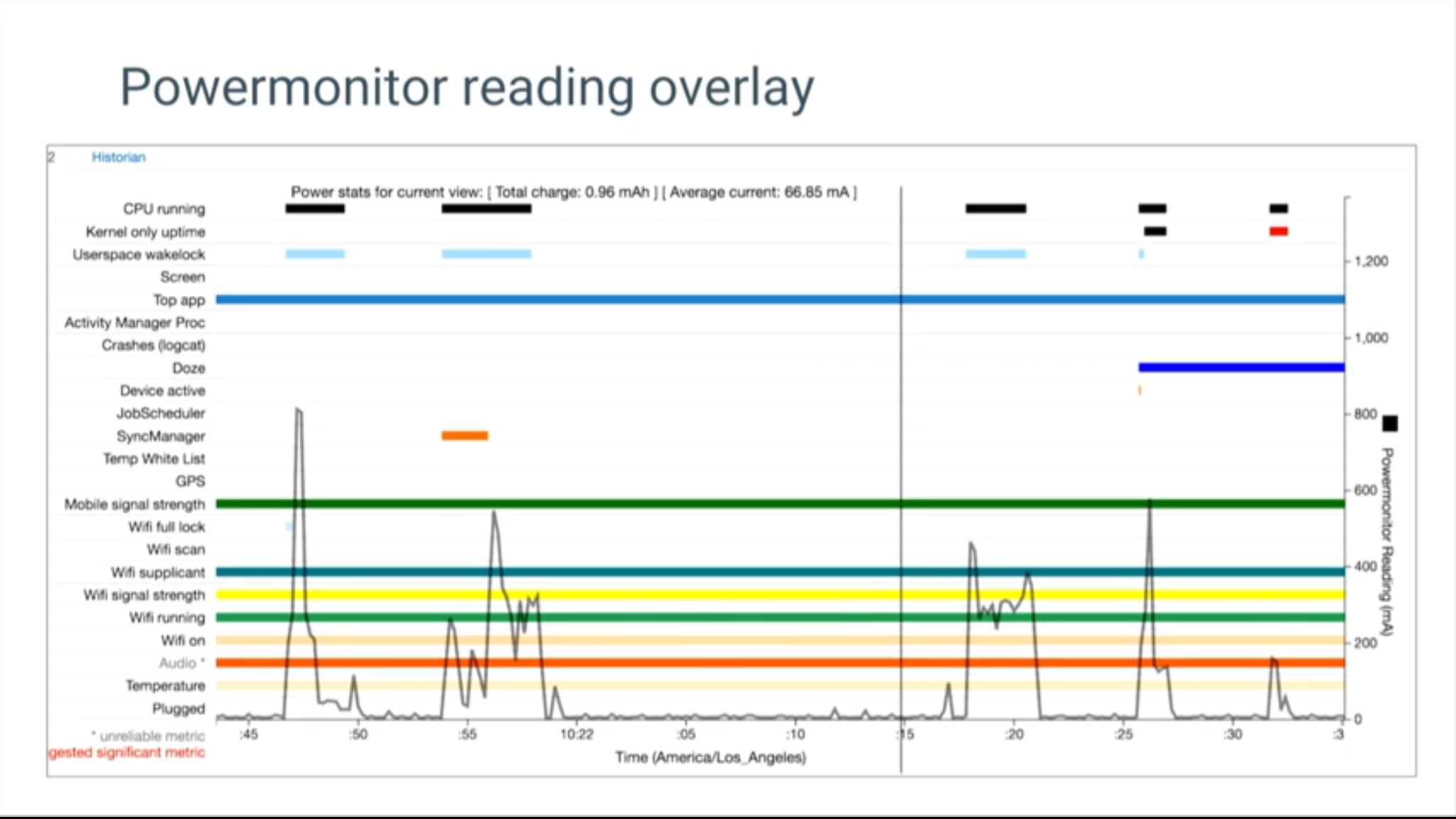

- Use case for Power monitor

If you were able to modify your phone to connect it to a power monitor which record the instantaneous current values when the device was actually running. And then, upload the bug report and these power readings, these instantaneous current values to the Battery Historian tool.

And it will show you a nice overlay of what your instantaneous current draw was and what the device was actually doing at the time. At least, all of it comes together. When the CPU was running, indicated in the black bars in the top row, that’s when your instantaneous current draw was close to 800 milliamperes. But when the device was in suspended, it was hardly anything you can’t even see it there, because it’s close to about 4-5 milliamps. So there are several orders of magnitude different in the amount of power that’s discharged from phone when you’re actively doing stuff.